Up until 15 minutes before we left the house to go trick-or-treating this Halloween, my 5-year-old daughter was going dressed as a medieval princess. Her biggest brother not only made her a crown with matching veil, he also whipped up jester costumes for himself and his younger brother so they could accompany her as wandering minstrels. It was all set. Photos were taken and everything.

But then, my daughter changed her mind. She no longer wished to be a princess. Now she wanted to be Tzietel from “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Well. That’s quite a thematic change, isn’t it?

I’ll admit, I didn’t see it coming. Even if we had just watched the classic movie the night before, the first time for all three of them, the 13-year-old and the 9-year-old, too.

What interested me most was how different each of their subsequent reactions was. Not just based on age, but on their distinctive personalities.

My 13-year-old son, who is in the eighth grade and thus knows everything and will be happy to tell you so repeatedly, was most concerned with Perchik’s fate. Did I think he’d die in Siberian exile along with Hodel, or would they return with Lenin and Stalin to join the October Revolution in 1917 and then be killed during the 1930s purges? (This is what happens when you let a boy with a Soviet Jewish mother read Animal Farm. And fill in the details of who’s who.) As for Feydka The Goy, was he a Kulak and so poised for extermination in the 1920s, or since he and Chava, at the end of the play, announce their intentions to move to Poland, would they actually stick it out until Hitler came for them?

On a more shallow note, he was also intrigued by The Tailor Mottl Kamzoil’s sewing machine, as a big part of his constructing the minstrel costumes was cutting down one of my old dresses into a jester’s vest, then hemming it, and the idea of a machine that didn’t thread it’s own needle seemingly upset him more than the upcoming purges.

The 9-year-old, of whom I’d say current events interest him about as much as events happening on the moon–except that isn’t true; if they happened on the moon, in space, or within a science lab, only then would they interest him–focused almost exclusively on the technical minutia of daily shtetl life. How did Tevya make his cheese? Where did Lazer Wolf the Butcher store his meat without refrigeration? How did the blacksmith put on his horseshoes? Why weren’t any of the candles in the wedding scene being put out by the wind? And what do you mean the bathroom is outside of the house?! For him, it was basically Little House on the Pale of Settlement. (The non-scientist, dancer version of him

did get up and boogie during the musical numbers. And he stopped and gaped while the Hasidim danced with the bottles on their heads. Then promptly attempted to do the same. We’re still getting the splinters out of his knees.)

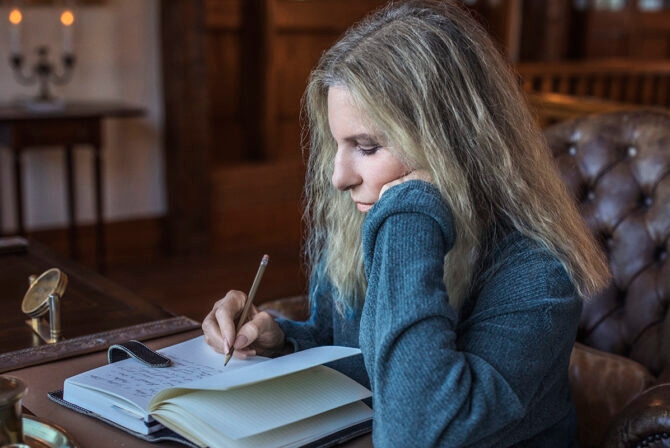

My daughter, on the other hand, sat mesmerized, chin in her hands, for the duration of the almost three hour long (two hours and 59 minutes, to be precise) movie, furiously trying to understand everything that was happening. Her first question came at the tail end of the first act.

“Who are they?” she wondered, as the Cossacks on horseback came to interrupt the heretofore joyous wedding.

“The police,” I told her.

“Oh,” my little girl, the born and bred New Yorker, pondered the possibilities. Then it hit her. “Were they making too much noise?”

“No,” I said. Just as the Cossacks began ripping up pillows and smashing cookery in advance of setting the entire village on fire.

“Why are they doing that?” she wanted to know.

“The King of Russia sent them. They’re his soldiers and he wanted them to scare the Jewish families.”

“Why?” Since, like my know it all oldest son, I also was aware of where the story was going, I decided to spoil the ending a little–and get her ready for it. “Because he doesn’t want the Jews living in his country anymore. He wants to make things bad for them so they’ll leave and move someplace else.”

“Like you did when you were a little girl, Mama?”

“Sort of.”

“So why did everybody stay there such a long time if the King was mean to you?”

“Not everybody who wanted to was allowed to leave.”

“But, I thought he didn’t like Jewish people and wanted you to go.”

“It’s complicated,” I agreed. And moved on to Act Two.

Twenty-four hours later, I guess she’d identified enough with her oppressed ancestors to want to dress as Tzietel. So, in 15 minutes, I dug up a simple cotton dress, a (bandana) head-covering that bore a striking resemblance to what my grandmother used to wear around the house, and a men’s scarf that could also serve as a shawl. Since it was a chilly, October night, I made her put on said ensemble over a pair of tights, a turtleneck sweater, and fur-lined winter boots. As my mother would say, “I didn’t come to America to catch pneumonia dressing like a peasant.”

While her outfit wasn’t as easily comprehensible as the Jedi, dinosaurs, and NY Yankees that we passed on the street, as soon as she explained who she was, more often than not, a neighbor would burst into a chorus of “Matchmaker, Matchmaker” or “Tradition.” It made my daughter very, very happy.

How much of the movie did any of them ultimately absorb? I don’t know. But, that’s okay. Like with the Holocaust play

I took my sons to last spring, it was supposed to be a conversation-starter. Not an ender.

If it’s that time to show your kids the classic, buy Fiddler on the Roof on Amazon, and a portion of the profits will go to help support Kveller. The soundtrack wouldn’t hurt either, right?