Let’s face it, aside Julia Quinn, the author of the romance series the show is based on, there is nothing Jewish about “Bridgerton.” Both the books and TV series focus around the eponymous family of nine living in Regency times and their complicated love affairs. (I’ll just say here that it’d be lovely to have some Jewish representation in a show that takes so many liberties with the original material, perhaps in an upcoming season? There were, after all, Jews in Regency-era England!)

But the show does focus on a topic that has a very central place in Jewish discourse: the power and the evils of gossip, or as it’s known in Hebrew, lashon hara.

The entire show, and the first four books of the series, center around the column of one mysterious Lady Whistledown, who shares the gossip of the town in her very popular rag. In the show, it’s so ubiquitous that it garners the obsession of the queen. While the series is a diverting, eye-pleasing and steamy romp (some complain not steamy enough this time around, but I have no such qualms), it does offer its own social commentary about gender and the cost of spreading rumors, be they founded in truth or not.

If you’ve never heard the term lashon hara before, it literally means “evil tongue” and is the Jewish term for talk that besmirches another person’s reputation and shares information that may put them in a negative light without their consent.

According to Leviticus 19:16, “You shall not go up and down as a slanderer [in some translations: talebearer] among your people.” Gossip is also frequently condemned in the Book of Proverbs.

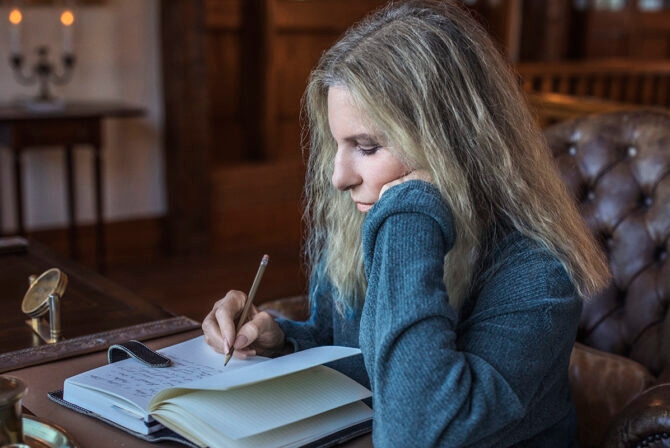

When we first hear from Lady Whistledown in season one of “Bridgerton,” she is an ominous mysterious presence, all-powerful, voiced by the incredible Julie Andrews. At the end of season one (spoiler if you’re behind!), Lady Whistledown is revealed to be Penelope Featherington, the best friend of Eloise Bridgerton and a wallflower played by the impossibly sweet Nicola Coughlan.

I watched the first season before I read the books (I have since read all of them, a thing I highly recommend) and I remember the absolute shock of seeing such a beloved and sweet character revealed to be someone who at times can be so venomous — who even went as far as to ruin her own family.

In the books, Penelope is BOOK SPOILER ALERT: only revealed to be Whistledown in the fourth installment of the series, “Romancing Mister Bridgerton” (yes, that’s the Colin Penelope book, and yes, it is one of the best ones). But there is discussion about her morality throughout the entire series. Penelope seems to have rules about things she does or doesn’t do; Whistledown, at least for Penelope, is never meant to be downright mean.

One thing is undeniable about gossip, especially for Penelope Featherington: It is a heady source of power. For Penelope, it is also a means to a livelihood — a gifted writer, she parlays her skills into a more-than-respectable sum that, at least in the books, gives her not only the possibility of independence, a thing incredibly rare for women of the era, but the ability to support her family.

In fact, it’s a realm where women can actually have power over men. Penelope has the reputation of the city’s most powerful men in the palm of her hand. Gossip in general is a space for disempowered people to feel autonomous — to feel like they have an impact and authority, especially when the information they are spreading is true but otherwise wouldn’t be talked about because of the social structures at hand. Am I saying that it’s a positive thing that Jewish women are often stereotyped as yentas, or gossipers? Not really. But the power dynamics at play are certainly interesting to think about.

But gossip does carry a price for the gossiper. In the second season of “Bridgerton,” we see Penelope paying quite a steep price for being Whistledown, losing some of the things that she cares about the most (no spoilers) to continue to run her column.

Ultimately, the show doesn’t really come down against gossip (it doesn’t help that Coughan’s Penelope is so absolutely loveable). But it does serve as a reminder that the sin of gossip, or lashon hara if you will, does not fall only on the gossiper. Both the teller of and the listener to lashon hara are guilty of transgression, as My Jewish Learning reminds us. Certainly, the gossip wouldn’t have its sting without the keen ears and eyes it falls on.

“Bridgerton” is just another reminder that the prohibition against gossip is extremely hard to follow. After all, the compulsion to share information is strong and oh-so-entertaining. For Whistledown, it is sometimes also a way to protect those she loves — from disastrous marriages or the ires of the queen. As I watch the show, I’m really rooting for Penelope, despite her imperfections. After all, she’s just taking advantage of a system to gain some measure of power, in a world where she feels so invisible.

But I’m not here to give anyone a green light to gossip. As a recent Israeli anti-bullying campaign says, “Lashon hara, ze lo medaber elai,” meaning “gossip doesn’t speak to me.” Even as a perhaps less observant Jew, this is one edict that I really aspire to.

So yes, lashon hara in real life? Can be harmful. Lashon hara in a Netflix binge? Just utter delight. Give me six more seasons, please and thank you.