The Supreme Court building that Ada Karmi-Melamede designed with her brother stands still, a miracle of modern architecture, embedded deep in the ground. But the ideals it stood on? It feels to Ada, in the documentary “Ada: My Mother the Architect,” that they are crumbling.

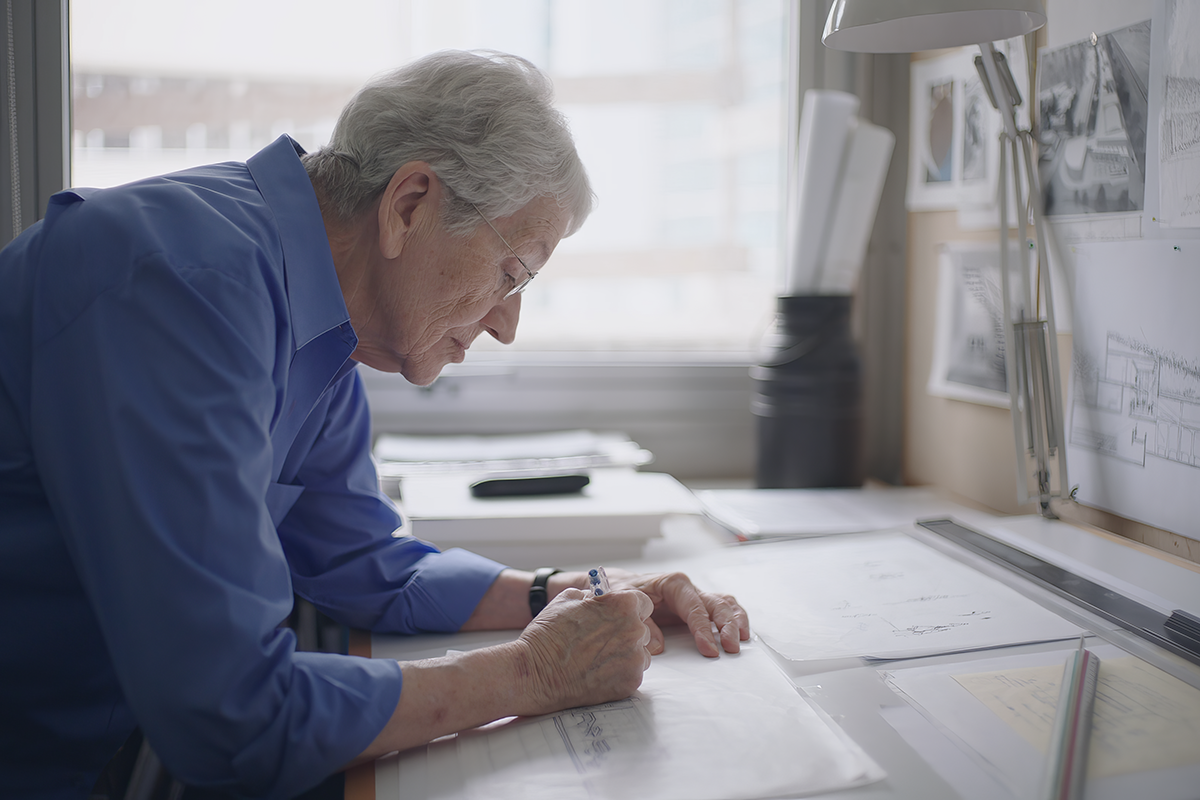

So many people think about their legacies: What is it that I leave behind? For Ada, who won the Israel Prize for Architecture in 2007 (the second woman to do so), the answer to this question is, in some ways, straightforward. She has left an indelible mark on the history of architecture in Israel: the new Ben Gurion Airport, Ramat HaNadiv Nature Park Visitor’s Center and her buildings, like those of her father before her and her brother, will hopefully always remain a part of the scenery of the country of her birth, the country she lives in now, oceans away from her children and grandchildren. And now this new documentary, directed by her daughter Yael, is also part of her indelible legacy.

You fall in love with Ada in the movie, like generations of students at Columbia University did over the 14 years that she taught there (and then she was passed up for tenure, perhaps because she was one of the few women on staff, the documentary gently alludes). But you also fall in love with her relationship with her daughter, who both nudges her and teases her and also clearly reveres and adores her. Going through pictures from her childhood, Ada isn’t always sure which of her daughters is in the picture, and there’s something about those moments that feel like they could be so wounding for a child. And yet it’s clear that Ada sees and loves her daughter, and perhaps most importantly, allows herself to be seen in this completely vulnerable way that I think shows excellent parenting. Here she is, sharing her entire life story with her child, and you can see her really measuring things not so much for her legacy, but for the sake of truth.

In the movie we see Ada commit what was, at the time, in the eyes of many, a cardinal sin for mothers: that of leaving her kids behind. After getting rejected for tenure, she moved her work to Israel, working side by side with her brother, iconic Israeli architect Ran Karmi (Ran, Ada and their father Dov, also an architect, all have won the Israel Prize for Architecture, the country’s highest honor in their field). Getting that Supreme Court contract meant she was contractually obligated to spend the majority of her time away from her three children, who still lived in the United States. Her daughters were teens at the time.

In a movie like this, with a daughter directing her mother, old resentments often resurface. But “Ada” isn’t that kind of film. There is so much fondness from Yael for her mother, so much humor and ease. And then there’s Ada, who, like any mother who has won has the greatest joy of all — being adored by her adult children — is almost incredulous. Her only question for her daughter is: How can you still love me after all these years? And she’s apologetic, too. She is not “a typical Jewish mother,” she says with bashfulness, comparing herself to her husband, Amos, who passed away in 1994, and who she felt was the better parent of the two.

“Ada” is all about legacies, and there is this legacy that Ada leaves behind as a mother, one that is more complicated than her physical buildings: the legacy of loving and connecting with one’s children, even if she was a working mom, so far away.

“I think she gave me a real gift as a woman, and as a mother, about not ever feeling guilty about working. I didn’t realize how special that was,” Yael told Lisa Keys of New York Jewish Week. As a working mother myself, I saw in Ada an illuminating blueprint of the kind of mother many of us would like to be: adored, respected, vulnerable, close. As an Israeli expat who lives far from her own mother and family, I also felt so seen by an old letter Ada shares at the end of the movie, a letter she wrote to Yael at age 20 in which she dreams of a life “where closeness is taken for granted and spontaneity is just there.” I too dream about being able to drive to my mother and embrace her that same day, but knowing that that longing exists is proof that the foundation of love is solid — as thoughtfully constructed as any of Ada’s design.

In the film, Frank Gehry and Moshe Safdie — some of the world’s greatest architects — reflect on Ada’s brilliance. They mention the way she has of speaking so clearly about building and about the nature of time itself. Those reflections feel as deeply rooted in reality as her buildings.

Which perhaps leads to another not-so-straightforward legacy for Ada: There’s the legacy of the country Ada help built, Israel. The country was meant to represent a kind of idealistic principles, and these felt imperiled at the time the documentary was shot. At that moment, in the midst of mass protests over Israel’s Supreme Court Reform, many Israelis felt abandoned by their country. That is even more true now. Ada and other experts in the film talk about her design with a bittersweetness; it encapsulates an ideal of Israel that feels more distant than ever.

In an old letter, written during a different time of upheaval for the country, Ada talks about feeling like she is “living in a bad dream.” She fears if Israel as a country is “going to emerge in one piece,” words that feel to Ada far more real in our current reality. Yael asks her how it feels to have that building — the Supreme Court — at the heart of it all. But Ada believes that her building is not at all a part of the issue, that the question itself is one of time and space that eclipses earthly structures. She fears whether Israel will remain a democracy or become a “dictatorship of some kind.” “I have to confess,” Ada says on camera, “that I have lots of tears in my eyes.”

There are many moments and images in this marvelously beautiful documentary that have stayed with me, but one particular line from that loving letter Ada wrote to Yael gnaws at me. “It’s important for you all to find a place for this place in yourself,” Ada tells her daughter in that letter. She is of course referring to Israel, and it has me considering the legacy I, as an Israeli-American, will instill in my children about Israel. I know many Jewish parents are grappling with this same question. What place for this place will our children find in themselves? And will that place have the same magic and wistfulness encapsulated in “Ada: My Mother the Architect”? I hope it does.