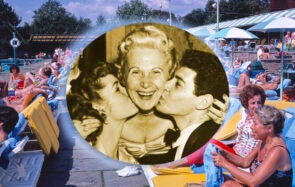

I own a flamingo menorah. It decorates the lawn outside my house each December. (And, in years like these, November too.) It shares the space with an inflatable penguin, waving its arm amicably, dressed in a snowflake sweater and a Santa hat. Beyond the mezuzah and the open door, the dreidel stocking from my childhood hangs beside my husband’s Christmas one, his name embroidered at the top by his mother’s hand. The Christmas tree beside it nearly touches the ceiling, adorned with dreidels, menorahs, shaloms and chais, alongside plaster imprints of the kids’ hands at age 2 and the “Our First Christmas” Mickey and Minnie ornament with the chipped nose.

Some will read that description and see me as Jewish in name only, responsible for the commercialization of a minor holiday to make it into something it’s not.

Or, as I was told in Hebrew school, one of the assimilators killing the Jewish faith, finishing the job Hitler started.

As if our faith could be murdered by love.

I am the granddaughter of survivors who never, ever spoke of what they escaped. I am from a grandfather born into Brooklyn tenement halls, one-room apartments so packed he was bitten by a rat as he slept in the drawer by the fire. A man who grew up to take me to the temple to have me named in the old way, without my parents present. I am from a great-grandmother whose name I carry and I know only through my father’s eyes and her handwritten recipe cards for matzah ball soup. I am the goddaughter of the pious and feisty Sicilian Roman Catholic woman who loved deeply but God forbid she give you the horns. I am from the father who built me not one but two giant electric menorahs that he planted on the lawn, from the mother who converted our Hanukkah bush to a Christmas tree the year I brought my husband home, “to make him feel comfortable.”

My husband is from circus performers and farm men, WWII vets who fought to give my family our freedom, twice-baked potatoes and hot dogs over the fire on Christmas Eve. From families of six, seven, nine children, so many red-headed cousins they share their names as they pull me into a hug. From accordion players and boat-builders, artists and academics, and the branch who love me without question but who, until I sat in their living room, had never met a Jew.

I felt like an imposter when asked to explain what we believe. I remember all the times I have been told, explicitly and implicitly, that because I’m also adopted, I’m not really Jewish, despite what I know is in my heart.

I know I am a mishegas of Christmas trees and Santa’s laps and Purim carnivals and Kabbalat Shabbats. I am both the girl who boycotted her own bat mitzvah and the woman whose most meaningful moment of the year often comes during tashlich service, rarely led by a shul. I may appear more Jew-ish than Jewish, but it is the practice of tikkun olam that guides who I am and how I live.

I knew when I married a man whose middle name was “Christian,” we’d have to get creative to discover what felt right to us. This year will be our 18th — chai! — wedding anniversary. Our love will be old enough to vote. And we’ve voted with how we’ve lived, creating untraditional traditions that, as our ketubah says, established a home that is compassionate to all.

My husband makes a better matzah ball soup than the kosher butcher in our family. He’s the one our local Chabad called to decorate its windows. Our pre-COVID Passovers looked like gigantic romps filled with friends and haggadahs we wrote ourselves, mapping the Four Sons to pop culture icons like The Beatles and Chewbacca, always starting with the Muppets. On Rosh Hashanah, after we go apple picking, the kids make a mess dipping the fruit in a flight of honey, and we gather around YouTube to watch the Maccabeats’ newest video and our favorites from years before. (Nothing tops Aish.com’s Rosh Hashanah’s Rock Anthem.) On Shabbat, we light the candles and say the blessings, filling our gratitude jar with our updates from the week.

Sometimes my children and I express our Jewishness in a synagogue, both in-person and online. Via Facebook Live, I watch a lot of services from the first temple that felt like home, the one where I said Kaddish for my parents every week. We can also be found celebrating the holidays and living the values through a hodgepodge of local Jewish groups, each providing a thread of the fabric that knits together what my Jewish practice is evolving to be. It is the start-up collective that’s forming around me and our interfaith Jewish group where I feel the most myself, where I don’t have to wonder if my Judaism is enough.

I want there to be room for me, for us, in Judaism. Where I don’t have to ask the rabbi if I count, if my love matters. If our inherently Jewish values matter. If my children matter.

But I can’t wait for Judaism to answer me. I parent my children like my parents did me: We matter. More importantly, we are loved.

It is my 12-year-old daughter, who writes in her own poetry, that she is from sufganiyot and Danish butter cookies. She is from my husband and me, a world where Santa penguins live beside flamingo menorahs and both are celebrated for being exactly what they are. It is my hope that the Judaism of her life, of her brother’s life, will recognize that even though their quirky Jewish practices — these traditions formed around them with good intentions and a prayer — may look less traditional than traditions, that they, too, are shamashes, bringing light to the darkness.