Jason Gould’s voice is otherworldly, angelic almost. And while the Jewish singer, who is, yes, the son of Elliott Gould and Barbra Streisand, is not traditionally religious, spirituality has a profound presence in his life and music. So it’s no surprise that the title of his addictive and nostalgic new EP released last week is “Sacred Days.”

In the days before and after interviewing Gould, different songs from the EP keep finding themselves stuck in my head, from the sensuous club-worthy “Laws of Desire,” which has a delightful futuristic video that Gould helped create, to the sassy “Run,” which is perfect for anyone looking to dance out their rage for a toxic ex. Then there’s the magical journey and post-apocalyptic landscapes of “Sacred Days” and the angry rallying cry about the state of the world in “World Gone Crazy.” There are lots of nostalgic notes of the ’80s, ’90s and early 2000s in these songs, but they’re also very much singularly Gould’s.

“I’m a product of everything that I’ve loved,” he tells Kveller, “and then there’s a magical part — you just don’t know where things come from in terms of melodies and ideas and lyrics. It’s spiritual.”

This EP is different from Gould’s previous offerings, which are filled with the kind of epic ballads and sweeping covers of standards that his mother is known for. In fact, Gould has even collaborated with Streisand on one such song, a rendition of “How Deep Is the Ocean,” a 1932 standard by Irving Berlin.

“It’s a lovely duet,” he says about that cover with obvious fondness. People often tell him that the song means a lot to them, especially as a collaboration between a parent and child.

When I ask if his parents have listened to his newest release, he tells me, “I know my father has. He definitely likes Jason Gould. And my mother, I think, likes some of my music, but I don’t know if she can really relate to this more contemporary thing that I’m doing. I don’t know if that’s really her thing.” Whether or not it’s her thing, she can be seen kvelling about it on social media.

Gould’s voice is as comforting and mellifluous when he speaks as when he sings. His music is his own, but his approach to the business around it is very much shaped by the experiences he’s had being in the public eye from the moment his mother’s pregnancy became known.

“I’m not ambitious in a conventional sense,” he tells me. “I don’t particularly care for show business. So I do it in my own way. I do it because need to create. I love to create, and I love to collaborate. But the business part of it, which I’ve also seen my whole life — it can be really ugly. I just don’t care for it.”

“I’m an oddball,” he professes. “I love to create music. And then it’s sort of like, this is my offering, putting it out there is what I can do.” It’s not such a rare approach for an artist to want to focus on the craft, rather than on the business of show, but few have had the kind of electrifying, overwhelming brush with the business from the very beginning that Gould has had.

While he cares deeply about how his music can touch people, he’s not so interested in touring or performing in front of crowds.

“I toured with my mother,” he explains, filling big concert halls and singing with her on stage in 2012. “So I had that experience, and I had certain charitable opportunities to perform, which I did. But what I found is that I don’t like being in the spotlight.”

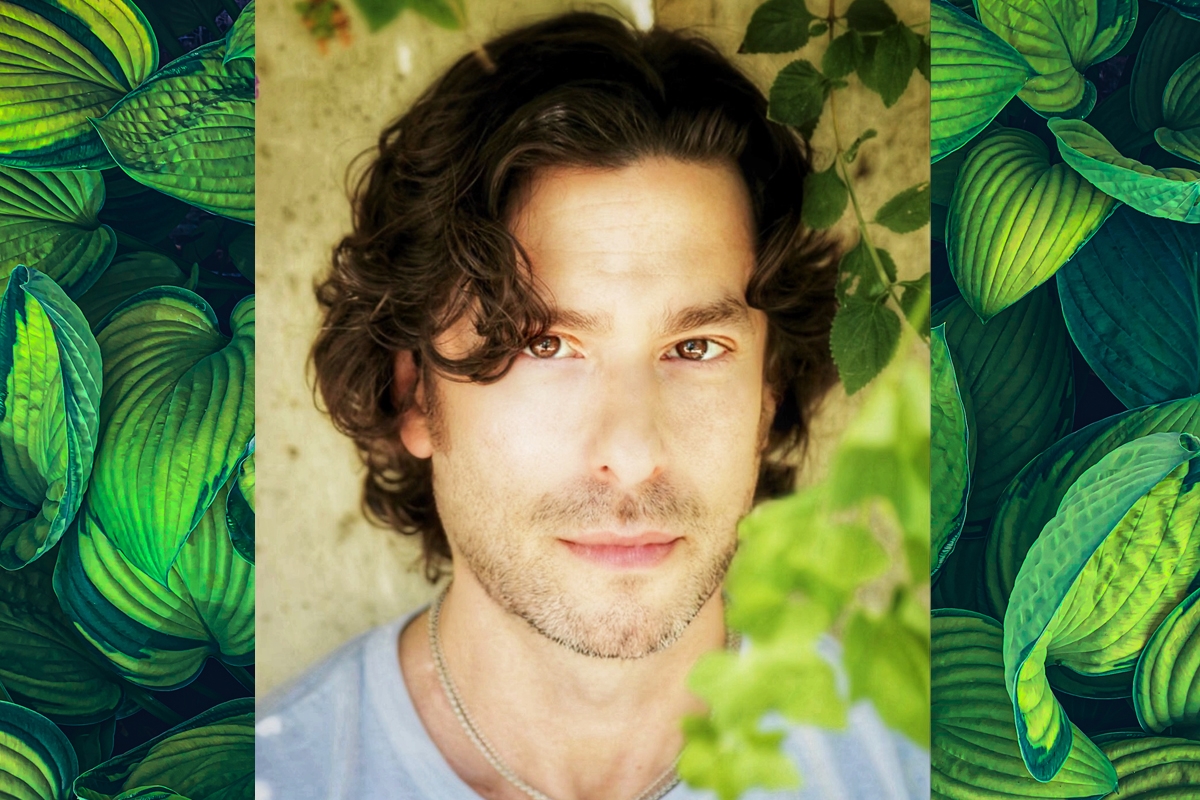

The earliest images of Gould as a child with his mother are cherubic almost, and his face is still that, with loose curls and kind eyes. Growing up in fame is something that he “struggled with a lot,” but growing up in a creative environment was something he has always loved.

“I made short films since I was a kid… and I was always playing the piano and creating melodies when I was quite young, so it’s just a part of my DNA,” he tells me.

Gould grew up with the music of his mother’s many projects, but outside of her work, he says she “never sang around the house.” When he was with his father, actor Elliott Gould, they bonded over music. “He liked music that I liked as well. I remember hearing Stevie Wonder, Mark Day and Jimmy Cliff. I’ve been exposed to a lot of music… and I would have periods of my life where I would dive into certain genres of music and then move on to others.”

Whether it’s making music or movies, it’s all about collaboration for Gould. “You can’t be too attached to anything… otherwise, I think you get lost.”

“My mother is known for her striving for perfection, but I don’t think perfection exists,” he explains. “We strive for as good as it can be. And then at some point, we have to let it go. I’m not a tortured soul. I don’t know that she is either. But maybe it’s something that she’s overcome.”

Gould had a bar mitzvah and has fond memories of his more observant maternal Jewish grandmother. “She made great tzimmes, which I loved,” he recalls. “Being Jewish… it’s a part of me for sure. But I don’t consider myself religious. I consider myself spiritual. I respect everybody’s beliefs.”

The idea of intergenerational trauma is deeply activating for him, especially as a person who has spent a lot of time working on himself. He thinks often of his grandparents, who all came to America from Eastern Europe, who survived “pogroms and persecution” to come to a country they didn’t know, where they had no grasp of the language or work prospects lined up, where they never spoke to their kids about the trauma of antisemitism.

“I feel a lot of compassion for my ancestors, because I know that they suffered. Even within my own family, my mother lost her father when she was an infant, you know, and that’s a big trauma. And I know my father’s mother had a very rough life. Her mother died when she was quite young. I don’t think a lot of people think about or talk about it, but the trauma of our ancestors affects us.”

To him, the “only way to heal is to help other people and to make something of the pain.”

“I think that’s what makes artists become artists; it’s because they know pain. They’re touching on something that some people can’t even think about, let alone acknowledge within themselves or their own families.”

One place where Gould addresses that kind of healing — and the idea of tikkun olam, or the Jewish value of fixing the world — is in the track “World Gone Crazy,” in which he takes on many of the political issues his parents have been known to take on, including war, proliferation, misinformation and reproductive justice. “Both my parents are proud liberals,” Gould says, and “both care deeply about equality, justice, and I do as well. It’s not something that I necessarily was taught. It just felt right to me.”

The song was written long before October 7, but he incorporates images from the aftermath of the attack in Israel, as well as from Gaza, alongside images from Ukraine and other war zones throughout the world.

“I didn’t go into the writing session thinking I want to write a song about the state of the world,” Gould says. “I didn’t want to be political in [the video], and yet, I guess you could say it just is political.” The video takes aim at certain politicians in the U.S. and the world, from Trump to Putin. “I was just looking at it from the humanistic point of view… There are children that are suffering, people that are dying. Is this who we want to be? Is this who we are?” For Gould, the song is about “pointing out hypocrisy” and “decrying misinformation.”

From wars to gun violence in this country, Gould is impacted by it all. “I’m upset and devastated and angry and sad about it… But what can I do other than be a voice as an artist? That’s my offering. And I can I vote. And I give money to causes that I care about and candidates that I think are good. But I know I can’t change anyone’s mind. I can just do my part.”

For Gould, the idea of social justice is deeply connected to the kind of inner work that we have to do for ourselves.

“I know that I can’t change other people. I can’t change the world, but I can be a voice of compassion, reason and love. It begins with you. You can change the world by changing yourself or by being what we want in the world: by being in integrity, by being honest, by being compassionate, by being good.”

“It’s an inside job, it starts with us,” he says. “There’s a huge swath of human beings who don’t do that work, who aren’t willing to look inside themselves and take responsibility for their beliefs — for their hatred, for their judgments.”

Whenever I try to ask Gould about artists he’d like to collaborate with, or celebrities he admires, he gently nudges me away from those questions. “I’m not terribly impressed by people just because they’re famous. For me, it takes other things to impress me, like [being] a good person, someone who’s kind, someone who has integrity, someone who’s compassionate. Those things impress me, but someone’s fame — eh! — there are some real assholes out there who are famous. I don’t find that wonderful.”

His relationship with his parents as an adult now is very honest. “I’m a no bullshit kind of guy… I’m the same with my friends and my parents… It took me a while to get there. I wasn’t always like that. But now I’ve done the work on myself, where I know who I am. And I’m not afraid to be who I am,” he says. “I have to be honest with myself and with people — love me or leave me, but I have to stay in my integrity.”

You can listen to “Sacred Days” on Apple Music and Spotify