Most of us know about Elie Wiesel, the Romanian-American Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner, whose memoir, “Night” is one of the most studied books about the Holocaust. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 and spent his life dedicated to championing peace, understanding and human dignity.

Yet most of us never had the opportunity to actually meet Wiesel, who passed away in 2016.

But a new documentary, “Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire,” gives us an opportunity to feel like we have. It’s an incredibly intimate and spiritual portrait of the writer, taking us from his childhood in Sighet, Romania, through the harrowing experience of losing that home and his family in the Holocaust, and then through the rest of his life.

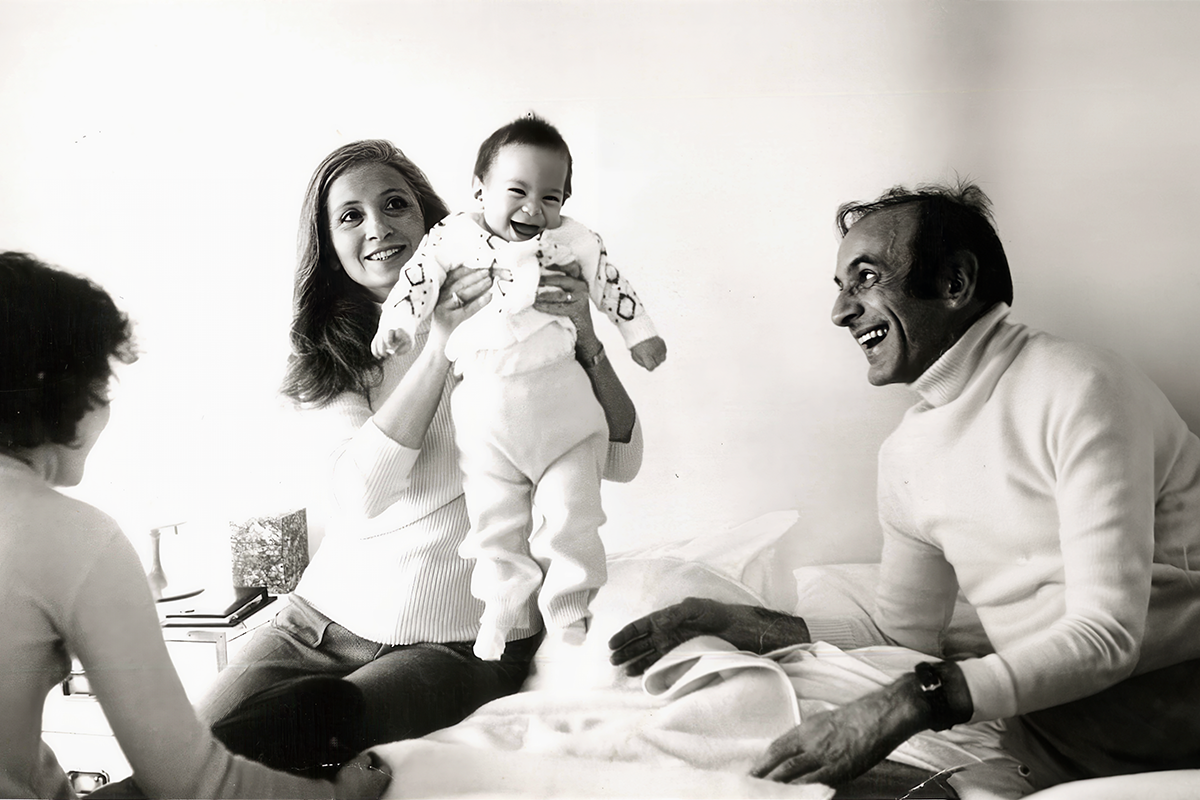

Director Oren Rudavsky, who has previously brought us documentaries like “Hiding and Seeking” and “Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People,” was interested in resurrection when thinking about this film. He brings Wiesel back to life to narrate his own story through recordings and arresting videos and stills, but also through painted animation, which seems to bring Elie’s very soul to life. He shows us a man who was deeply connected to family and Judaism, a man who lived always with his slain loved one weighing on his soul, a man who loved Shabbat and Jewish tradition. He even offers us a chance to listen to Wiesel chant a Hebrew prayer, channeling the voices of his ancestors like an oracle.

Kveller talked to Rudavsky about the creation of the film, why he wanted it to feel like a personal conversation with Wiesel and the final message Marion Wiesel, Elie’s widow, left him about the project before she passed away in 2024.

Tell me a little bit about how this film came to be.

I had a meeting with Marion [Elie’s widow] and Elisha [their son], who had seen a previous film of mine called “Hiding and Seeking,” and which they loved, especially Elisha. We discussed how we could make this film, and I said, we need complete independence. This needs to be our film, but your cooperation is vital to making this the kind of film that will reveal Elie Wiesel in a new way. And so they gave us that consent. We wrote up a proposal [saying] this film, in effect, will be narrated by Elie Wiesel. It will be in his own voice and we need access to your personal archives, and we need to film you all, and that’s what we did. It [was] a four year process.

It really did feel like you resurrected him in this film. I also did not expect the film to be quite so spiritual.

Thank you for saying that, because I feel like that’s really the through line: his emotional core, and how that gets passed on to the generations.

I found his grandson, Elijah, was so wise in this documentary. We meet him when he leads us on a visit to Elie’s hometown of Sighet. What was it like being there with him?

When I first met Elijah, he was 15 or so, and when we went to Sighet, he was 17. He had matured quite a bit. There’s a shot of him in the film where he looks so much — aside from his long hair — like his grandfather. Their look, and also Elijah’s gentleness, is similar.

Initially, I was asking Elisha to go to Sighet, and Elisha said, I can’t go, but Elijah can go. And that turned out to be a great inadvertent directorial idea.

It felt very purposeful!

Yes, very purposeful. That journey was really wonderful. We went to Romania, to Sighet, where Elie was born and where he lived until the age of 15, when he was deported. We went to the site of the synagogue there, and then walked around the town, and, of course, went to his home, which still stands. It’s now a museum.

We found footage of Elie as well — in front of his family home and talking about what it was like to go back to his hometown. And in it, Elie speaks about the cemetery in Sighet being the only place that still feels to him like the Sighet that he grew up in. And we went there with Elijah to try and find his great-grandfather… we wandered that cemetery quite a while with the director of the Elie Wiesel Museum. There’s a wonderful scene, which I don’t want to give away completely, in the cemetery towards the end of the film.

Ancestors matter so much to Elie and to Jews in general. Many societies revere their ancestors. So going back, Elie speaks so beautifully about wanting to connect with his father and mother and baby sister who passed away, and that is part of the spiritual arc you’re talking about, and his soul of connection to his community.

I also love the language of the animation in this movie. It’s not realistic — it is in that spiritual vein — but it is very much alive. Tell me a little bit about the choice behind the specific animation and the use of animation in general.

Joel Orloff [who worked on the film] is a young and extraordinarily talented animator. We talked about the Jewish animator William Kentridge, who’s South African, who draws with charcoal in his animation and then smudges it. And what that evoked to me in that work was memory — that you can erase things and put them back and smudge them the way you remember things, not necessarily completely clearly, but evocatively.

We worked with paint on glass, which is similar in that you can move the paint around with water, with your hands. We played with that, and I just thought it was so beautiful. It’s hand-drawn… We added more and more animation, because we wanted to bring to life, without the brutality of actual images from Auschwitz, what happened there to him. We also wanted to include his deportation to Buchenwald, and his father’s passing. So it ended up being 15 minutes of animation; anybody who knows how painstaking that process is, knows how hard that was. It was the last thing we finished, just weeks before finishing the film.

There’s that line that Elie says about writing a novel versus a Holocaust story. I’m wondering how you were thinking about the tension of telling a Holocaust story and making a biopic?

I believe in making films that are grounded in personal stories, and so the richness of this was that we had access to these private interviews that Elie gave. The genius of Elie — and this is not my genius, it’s Elie’s genius — is that whenever he was talking to people, he was talking to that individual, to that person. When he met with his students, with the thousands of students he had at Boston University, he made sure to meet each of them privately, even for five minutes, and people would come out of those conversations transformed.

Elie believed in the power of one person talking to another as a messianic moment. And so that was my guide in making the film. I tried to make it so that every person in the audience would feel like Elie was speaking to them. I was speaking to them. So it’s a Holocaust film, but it’s [also] a film about community and kinship and comfort in these very difficult times.

I love the scene in a school in Newark — North Star Academy Charter School of Newark — when you go into a 7th grade class to hear students discuss “Night.” They all connected with it in these really powerful ways and had amazing insights. Why was that important for you to include in the film?

Elie was a teacher. And I know that teaching was primary to Elie. Before the war, he always thought he would be a rabbi, which means teacher. He was committed to future generations. Whenever people wrote to him, by the classrooms, by the thousands, he made sure that every letter was answered. Students and young people were essential to him.

I wanted to make clear that “Night” wasn’t just being taught in Jewish schools. It’s being taught around the country, like in this is a school in Newark, New Jersey, with a multi-racial mix of students. I heard about this school from a young man named Todd Levine, who teaches at that school and who was part of my Saturday Shabbat study group. I asked, by chance, “Do people teach “Night” in your school?” And he said, “Not only that, it’s a huge part of the curriculum. We spend five weeks studying ‘Night’ as part of a larger curriculum on the concept of freedom.”

Marion talks about Elie’s relationship to Israel in the film. Obviously, the movie is coming out at a very complicated time for Israel and for Jews across the world. Why do you think a movie like this is important at this moment?

Elie was a strong Zionist throughout his life and a believer in Israel. He made a point of never being critical of Israel in public. That is who he was. For Holocaust survivors, Israel was a place of refuge.

He passed away in 2016. I have no idea what Elie would have said about the present moment. There’s no way of knowing. But particularly at Jewish film festivals, I noticed this palpable sense of comfort in [hearing] a voice of such compassion and understanding. Elie cared about all human beings, Jewish, non-Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Israeli, Palestinian. He wanted a world in peace, where Jews and Palestinians would not be killing each other; as he says [in the film], too many lives have been lost. So I’m sure he would have been outspoken and vocal and would have been grappling with the realities of the day with every fiber of his being. As to what he would have said or done, I simply do not know.

I do want to say one thing. In conversations with Elisha about the film and about his father’s legacy, one thing that we said early on was that whatever Elie would have done, he would have tried to bring the Jewish people together; the Jews in this country, in Israel and around the world. That would have been a main part of his mission.

Has his family seen the movie? What are their thoughts?

The family saw the movie, and they were all there, along with many of the kids from Newark at a screening at Lincoln Center for the New York Jewish Film Festival. Marion sadly passed away two weeks later. But she said to me and to others at that screening: “I love the film. It made Elie come back to life again for me. I fell in love with him again.”

“Elie Wiesel: Soul of Fire” is out in select theaters now. You can find screen times here.