Although I am the half that’s not Jewish in an interfaith marriage, my husband never put conversion on the table–not until I brought the question up on my own, three years after we got married.

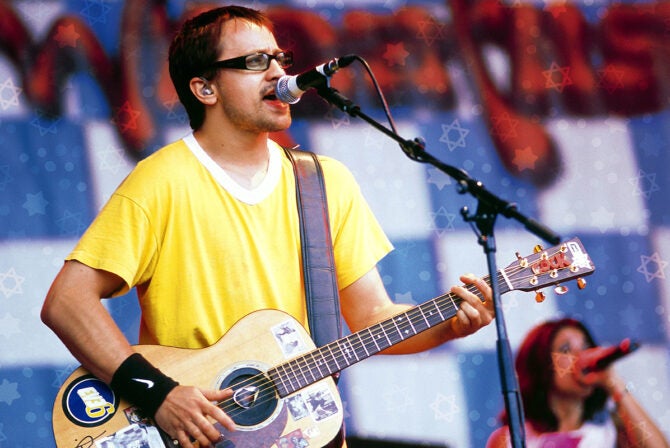

Shortly after my husband and I first started dating, Ben brought me to Friday night Shabbat services at a large Reform synagogue in Boston. A cantor with a guitar led the congregation in a wordless melody at the beginning of the service, and as the service progressed into as-yet-unfamiliar Hebrew phrases, I appreciated his help guiding me through the prayer book, not all of which offered transliterations of the Hebrew.

Afterwards, we drank small cups of Manischewitz and ate tiny chunks of challah at the oneg. He led me excitedly past cases of shimmering, evocative Judaica: menorahs, kiddush cups, haggadot with messages such as the feminist haggadot or “Haggadah for the Liberated Lamb” (a vegetarian Passover classic). Afterwards, we went out to dinner at a Thai restaurant, holding hands across a table and talking about religion.

Conversion wasn’t on the table that night, and it wasn’t even on the table when we became engaged, and then married. The only thing truly on the table that night, and in the nights since, was our desire to choose each other, and by doing so, to choose love.

Five years after that first date, three years into our marriage, though, I almost converted to Judaism. I’d attended a friend’s conversion ceremony, and during the joyous celebration of her joining the people of Israel, I found myself unexpectedly and profoundly moved by the experience. She converted in a Reconstructionist synagogue, and in keeping with the vision of Reconstructionism’s founder, Mordecai Kaplan, of Judaism as a religious civilization, the congregation emphasized a joyful spiritual approach that offered no insult to the modern intellect.

When my friend stood on the bimah and received her Jewish name and held the Torah in her arms, my mind flashed forward to times when I’d seen babies dedicated in the synagogue, being welcomed into the Jewish people. I realized, in a flash, what it might mean to hold my own child, and welcome her into the Jewish people, when I myself was not Jewish. There, in that room, with the resonant Hebrew prayers resounding throughout, it seemed that perhaps the covenant could extend to me as well.

I returned home and bought books about conversion, about Jewish ritual, about interfaith families. I listened to all of the major prayers on YouTube, and wondered how long it would take to do formal morning and evening prayers. I whispered the Shema to myself, imagining that my Jewish husband would look at me as if I were “going frum,” a somewhat pejorative way of referring to becoming overly observant.

A few days before Valentine’s Day, I couldn’t keep my curiosity in any longer. I wrote Ben a letter, explaining, in convoluted, circular words, how drawn I felt to Judaism at that moment and how much I appreciated many aspects of his religion. I gave the letter to him at breakfast on a Saturday, and the question of conversion now glimmered there between our held hands, right there on the table. He looked up at me with tears in his eyes.

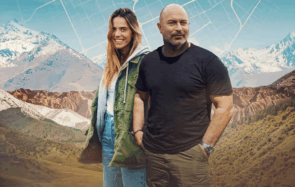

That afternoon, we went on a hike in the mountains near our home, holding hands, marveling in the wonder of the world we live in, and wondering what it might be like to have a religiously united family.

A few weeks later, I found myself in New York on a Friday night, and decided to attend services at a historic synagogue on Fifth Avenue. I had never been in a synagogue that so closely resembled a cathedral before: soaring ceilings, gilded walls covered in elaborate mosaics, and at the back, a Star-of-David “rose” window and a very impressive organ. A professional choir, accompanied by the organ, sang the prayers, while the well-dressed and equally well-heeled congregation listened in aesthetic appreciation of the music’s beauty. I left feeling confused, out of place, wondering what had happened to that initial inspiration.

In the end, this “crisis of faith,” so to speak, lasted for a few months. I talked with my friend who had converted, with other friends, with my parents. All were supportive, but cautious, not wanting me to confuse one moment of inspiration with making the right choice for both myself and my husband.

I found myself coming back to several facts from which I couldn’t escape: Unlike some converts to Judaism, including my friend, I don’t (so far as I know) have Jewish relatives somewhere on the less-well-known branches on my family tree, other than my husband’s family. In addition, although I appreciate Jewish religion and culture, my own understandings of religious culture, if I’m honest with myself, were shaped in the liberal, liturgical church in which I was raised.

It wasn’t an easy choice, mind you. I struggled with how to choose loving my spouse (and eventually, God willing, our children), with choosing a religion, and with being true to myself. I’d made religious choices for a significant other once before–choices I came to regret–and in the end, wasn’t willing to do that again, no matter how well-intentioned a similar choice might have been, this time around.

Throughout it all, my Jewish spouse stood steadfastly with me, choosing to love me every day, even if that meant we would remain an interfaith family. We knew, in the end, as the words on our ketubah had suggested, that we could choose love by letting each other be ourselves.

This article originally appeared on www.InterfaithFamily.com and is reprinted with permission. For more resources designed for interfaith families exploring Jewish life, visit www.InterfaithFamily.com.