“Dear YOF Community,” the letter from my alma mater began. “This afternoon, law enforcement informed us that Rabbi Jonathan Skolnick, a former employee of Yeshivah of Flatbush High School, was arrested on Friday for involvement in child pornography.”

My stomach churned as I read the news: Skolnick — the middle school associate principal at New York’s SAR Academy, and the Judaic studies teacher for grades six through eight — was arrested on charges that included receipt and distribution of child pornography, coercion, and sexual exploitation of children.

As a mother of a young daughter who attends preschool at a Jewish day school, I could not begin to imagine the horror parents at SAR in Riverdale and Brooklyn’s Yeshivah of Flatbush — where Skolnick had previously taught, from 2012 through 2018 — were experiencing.

I do not know Skolnick; our paths have never crossed. But as a Flatbush graduate myself, the sickening news really brought me back — and not in a good way.

Now let me unequivocally state that I have never been molested, abused, or the victim of a federal crime. However, as a girl growing up in the Modern Orthodox yeshiva world, there were always inappropriate teachers, rabbis, sleepaway camp counselors, and advisors. It almost goes without saying that these people were almost exclusively male, just as there were always students who knew the score.

I was in the eighth grade when I had two experiences with inappropriate teachers. The first was with my social studies teacher. He was a new teacher, a youngish man whom the students idolized. So much so that he had them over at his house on Sundays, and reportedly even took them to the local OTB — an off-track betting storefront on Avenue J near the high school.

When I complained to the principal about his behavior — did I mention he shamelessly flirted with the female students? — I was told I was the one who “had an attitude problem.” I was told I needed to change (likely true), and the teacher’s behavior was none of my business (definitely false).

All these years later, I do not know if our mustachioed social studies teacher ever did anything illegal or was just your basic, everyday creepy dude. When he taught my sister four years later, still a beloved teacher — but probably not hosting kids outside of school — he told her something like, “Good thing you’re not like your sister.”

Good thing, indeed. She didn’t have the same experience I had that same year with our mishna teacher, a gray, bearded rabbi with a reputation for “accidentally” brushing boys’ private parts. The boys in my class would reenact his “hugs” jokingly on Shabbat afternoons when we were all hanging out. Ha Ha. So Funny. All I had to share was the story of my Hebrew teacher, who told me I was “a waste of oxygen” and that I “just give carbon dioxide to the world.” (Good science lesson, though!)

Then, one day, at the end of the year, after an honors ceremony where I’d received a number of academic awards — though none for good behavior — he approached me in the hall.

“Esthayr Klein,” he called, using my Hebrew name. “When you grow up and your daughter comes home from eighth-grade mishna class and says she has a crush on her teacher, you can say you know what she means.”

“Excuse me?” I said, incredulous. “I don’t know what you are talking about.”

“Ah. Well, Estayr, let us keep this little secret to ourselves,” he said, adjusting the blue tie under his three-piece suit.

I did not. I did not have a secret to keep, nor did I keep quiet. I told everyone at school, so that later, when he approached another classmate about me, she told him she knew he was lying. But I did not bother telling the administration. What was the point? Apparently I was the problem.

I laid relatively low in high school, pulling my jean skirt down below my knees as I passed the male administrator who examined our bodies at the front door; avoiding the talks by the creepy math teacher who would ask boys about their sexuality; steering clear of the Talmud teacher who threw desks at (near?) students.

Creepy, abusive teachers were all around, in those days — and we, the students all knew it. But the question remains: Did the faculty?

In the pre-internet era, it’s hard to say what they knew back then. We know now that many authorities, religious or otherwise — from the Catholic church to the Boy Scouts to the Orthodox Union’s youth group, NCSY — have covered up all kinds of abuse. (For example, after years as serving in positions of power and working with kids, NCSY’s Rabbi Baruch Lanner was convicted in 2002 of molesting two yeshiva high school girls, eventually serving three years of a seven-year sentence).

Just last month, 38 men filed suit against Yeshiva University “alleging that the institution failed to protect its students from two rabbis who abused students in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s,” according to the Washington Post.

It’s awful, and I realize my collection of incidents are nothing compared actual abuse. Still, what happened to me inspired and influenced me to become a journalist, a feminist, and an outspoken voice to fight for justice.

And yet, I wonder how much has changed in our institutions, and I worry it’s not enough.

I am heartened by SAR’s swift response to the Skolnick arrest. The school’s principal, Rabbi Binyamin Krauss, sent an immediate letter to parents about the “horrible allegations” and the fact that students may have been victims.

Moreover, he encouraged parents how to talk to their children who might have been solicited, reminding them that they “are not in any trouble.” The school held an open meeting on Tuesday night for parents, during which guidance counselors and the FBI were present. “We will be re-enforcing our ongoing work of keeping our students alert and informed in an age-appropriate way, and will be reinforcing what steps they should take if they ever find themselves in a vulnerable situation in the future,” Krauss’ statement said.

I was less heartened by my alma mater’s initial response. In their first letter, the school stated they “were not aware of any type of inappropriate behavior during Rabbi Skolnick’s employment.” (Really? Come on, guys. He was at the school for six years, do you think his predatory behavior just started in Riverdale?!)

In a subsequent letter, however, they confessed they “received reports that some students were contacted inappropriately by an alias name that Rabbi Skolnick used.” Following SAR’s example, they held a meeting for alumni and parents on Wednesday evening.

Look, I am glad that the schools are responding to the heinous acts that were committed by Skolnick; it seems that some things, at least, have changed since I attended YOF in the 80s. Maybe today’s internet-savvy, connected kids are more comfortable coming forward. (Whereas my peers and I were always warned about “stranger danger,” kids today are far more aware of unwanted physical attention from people they know.)

And yet, I believe a school’s first response should be to protect its students. I’m happy that these awful crimes are being publicly addressed – they’re not sweeping them under the rug or shuttling faculty off to other schools and countries.

It’s a great first step. But it’s not enough.

It’s not just about addressing something horrible when it happens; it should be incumbent upon educators and administrators to prevent this sort of abuse from happening in the first place. It’s essential to more carefully vet each faculty member — use an outside consulting firm, perhaps? — as well as anyone who works with our children.

And, above all, we need these Jewish educators and administrators to listen to their students. It’s crucial to have systems in place for complaints, as well as for responses (we don’t want witch hunts, either). Above all, it’s essential for schools to have policies that make every single student feel safe and protected.

I think back to all of my yeshiva-going peers so many years ago, and how when icky or downright criminal things happened, so many of us felt powerless to speak out and, even more so, be heard. I hope the children of today will have more luck.

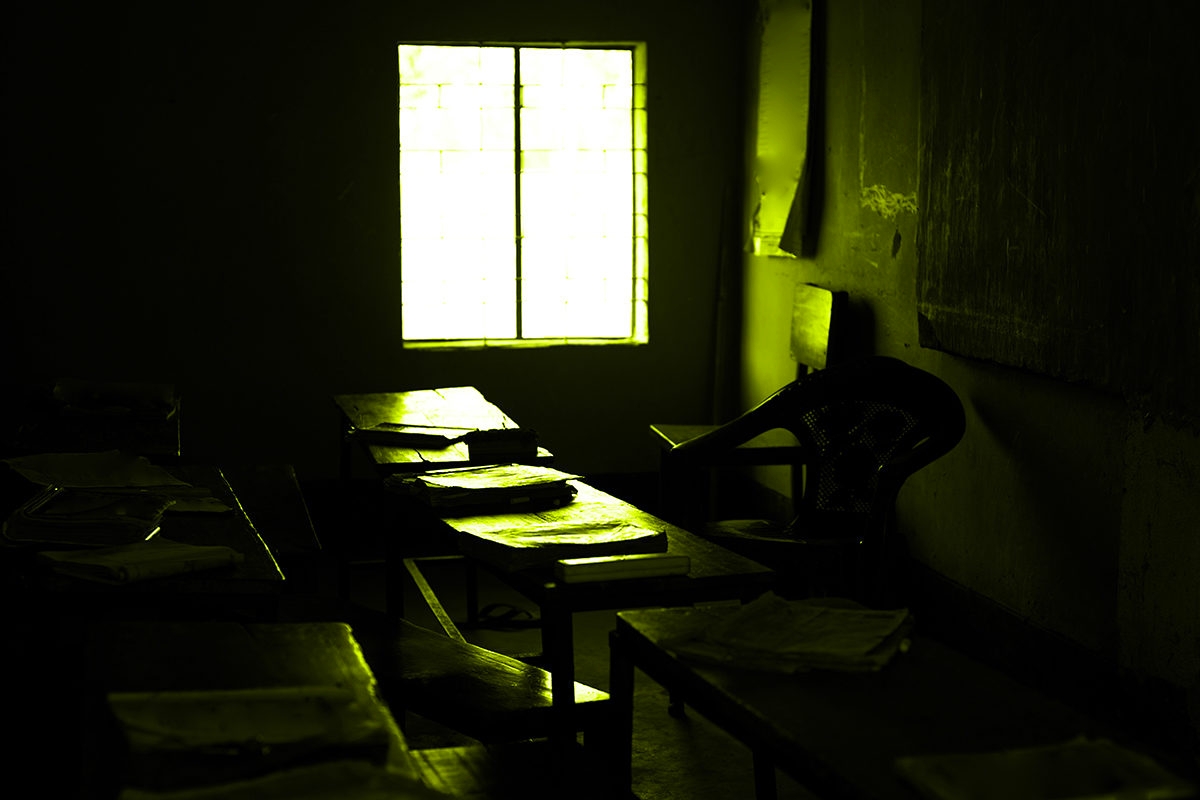

Image via Appography/iStock/Getty Images Plus