After the creation of the State of Israel, Jews from around the world flooded the newly founded country. About 700,000 Jews from predominantly Muslim countries (think North Africa, the Balkans, Central Asia and the Middle East) came to call the State of Israel home in the 1950s. They were often rendered stateless by governments that were hostile to them, and could bring very little with them. In addition to giving up homes, synagogues, documents and graves, they left behind friends to whom they could not return.

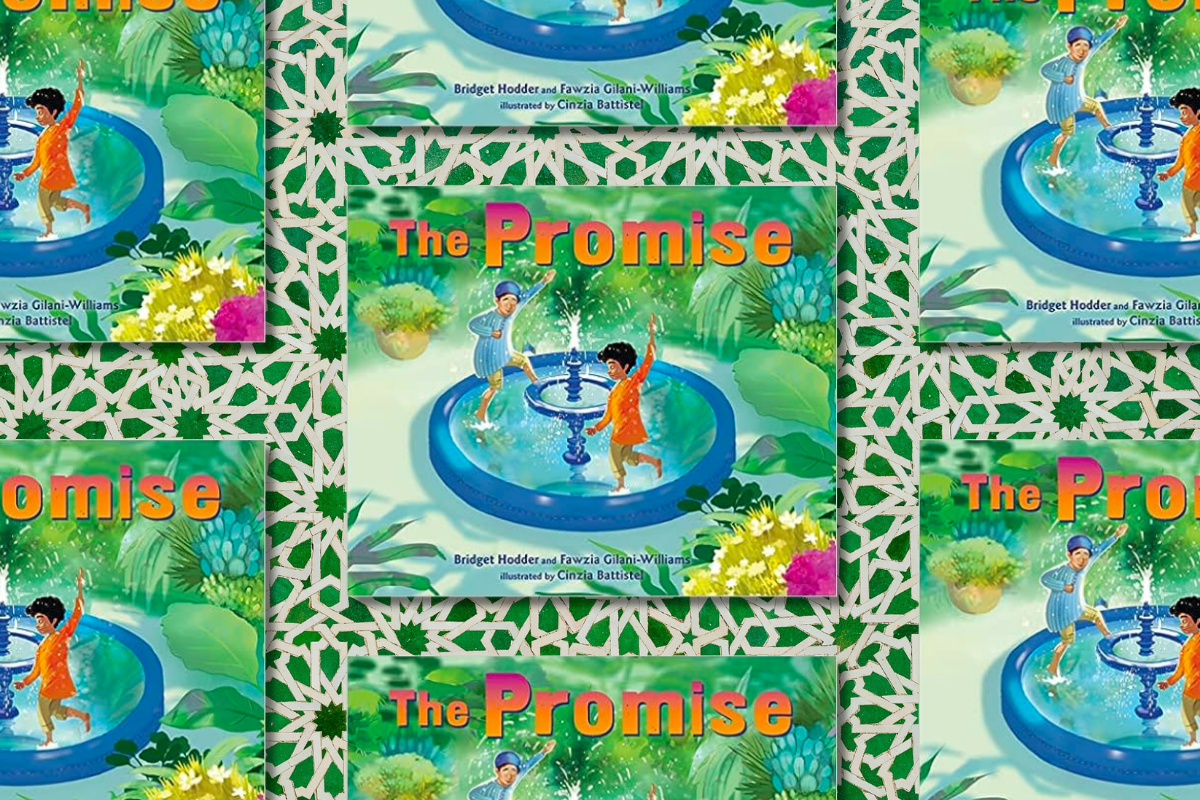

“The Promise,” a new children’s picture book from Sephardic author Bridget Hodder and Pakistani-Emirati author Fawzia Gilani-Williams, explores a world in which friendship is sustained across distance and the passage of time. Jewish Moshe and Muslim Hassan are separated as Moshe’s family flees Morocco during World War II, and are only briefly reunited in their old age. It’s inspired by a true story.

Over video chat, Bridget and I sat down to talk about the real-life inspiration behind the book and how it is providing an outlet for Jewish representation during a time of increasing scrutinization of children’s media.

Can you tell me a bit more about the real men who inspired “The Promise?” Do you know them personally?

“The Promise” is a co-authored work with Fawzia Gilani-Williams — we co-authored “The Button Box” before this. Fawzia is Muslim and she lives in the Arab Emirates. She’s a teacher and librarian there, and she writes and rewrites in global folktales for a Muslim audience. We met through our editor. After we finished “The Button Box,” she found a newspaper article in an Emirati paper that was about these two friends, Lahcen and Moshe, who were childhood friends in Morocco. I’m the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor and Fawzia’s family came to the Middle East from Pakistan after the partition of Pakistan and India, which was really violent. We were inspired by this story because we’re trying to highlight methods of peace and healing wherever we can find them.

When you’re writing a semi-fictionalized narrative about real people, how do you balance authenticity and a good story?

The original story was about a Moroccan Muslim man taking care of a Jewish graveyard. I asked Fawzia to draft her vision for this story, which turned out to be picture book length. It was more faithful to the original story, had that graveyard in it. Then we worked on the historical note at the end of the book together.

It could’ve been an upper middle grade novel and all of that [antisemitic violence, war] could’ve been grappled with on the page. For the feeling of uplift, we figured, we’re going to need to change that but make it clear in the historical note that we did that. We can still honor the genuine people — for that reason we changed the names and that’s basically how the departure happens. You tie things up in a bow in picture books that you wouldn’t do in older genre fiction.

How do you navigate talking about darker topics related to Jewish history with children of different ages?

I think that different age groups can handle different topics. Individually, some kids can learn darker things sooner. I do a lot of work against antisemitism. I do panels, I do workshops with my friends, for teachers and librarians on how to include Jewish content in public school contexts. One of the things we do is we try to give people a sense — read the book before you teach it. Then you’ll know if your class is ready for that. References to the Holocaust are appropriate in a general sense, fairly young. Actual Holocaust instructions — talking about the horrors of what really happened— I wouldn’t do until 7th and 8th grade.

For younger kids, what we want to do is casual Jewish representation. We want to see Jewish characters not portrayed in stereotypical and negative ways. We want it in books and in the media as well. We still see Jews being shown as rapacious or competitive, cutthroat. You begin with casual representation, you augment with general references and then you can really start grappling with tougher topics.

How does your Jewish identity inform your own work?

First and foremost, I want to keep alive and spread the word about Sephardim — who we are, about our wild and wonderful cultural traditions and language. After I published my first book, “The Rat Prince,” I noticed what was going on politically in the U.S. and I didn’t like what I saw as arising antisemitism, including permissiveness toward people being openly antisemitic. And I thought, it’s time to write the work about my heritage, my background, to honor my mother, my grandmother and the people that I love, and do so by connecting directly with children — because children are our future.

I can see that entire generations of Americans have not received the knowledge about Jews in general that they should be getting and I would be super wrong to not be a part of imparting that knowledge. Because I can. Muslims as well, were becoming objects of hate, they were being not allowed to come into the U.S. — it was crazy times. And the times have only gotten crazier. So that’s why I decided to write Jewish stories, specifically Sephardic Jewish stories, and even more specifically, I could not write about Sephardic history without including Muslim history, and to do that, I’m very dedicated to making sure that the Muslim present and past were properly represented. That’s how I connected with Fawzia.

This isn’t your first book about interfaith friendships between Jewish and Muslim children. Why are Jewish-Muslim interfaith friendships important to you?

My upbringing was complicated — my mom wanted to hide that we were Jewish, but be sure that we knew we were Jewish. All of my friends were Ashkenazic. So I felt as a kid, I didn’t understand why there were so many differences. I didn’t know Yiddish, I’d never had a matzah ball. The kind of culture I grew up with was very, very different. It had that component of Arabic and belly dancing.

The Ottoman Empire is the reason we still exist. My family left Toledo, Spain and moved to Salonica and stayed there until the Nazis came. Every single big group has its factions. It doesn’t mean they don’t still have very important things — history and community — in common.

Why was this story important for you to write?

Jewish representation in an era of book banning is so important for us to keep hammering. You have to keep up with it because it’s having a chilling effect. I’ve seen it. I’m out there on the front lines meeting with librarians and teachers. Honestly, behind the scenes, I’m afraid. In a time where one parent’s complaint can get someone fired or censured, this is getting very real. So my friends and I have developed tools that teachers can use and recommendations — casual Jewish representation, Holocaust books, teach this, not that. Rule of thumb — if you’re actually trying to satisfy curricular requirements with a Jewish book about the Holocaust, allow us to suggest they be written by Jews. We must support librarians and teachers more.