My grandmother used to pause for extended moments, trying to find the perfect word. The silence would make us uncomfortable and jittery, and my dad was quick to come up with suggestions while she searched her brain for the most fitting adjective. It wasn’t her lack of clarity of mind that caused this — she held as steadfast to that as she did to her last breath at 95 years old. It was her emphasis on precision.

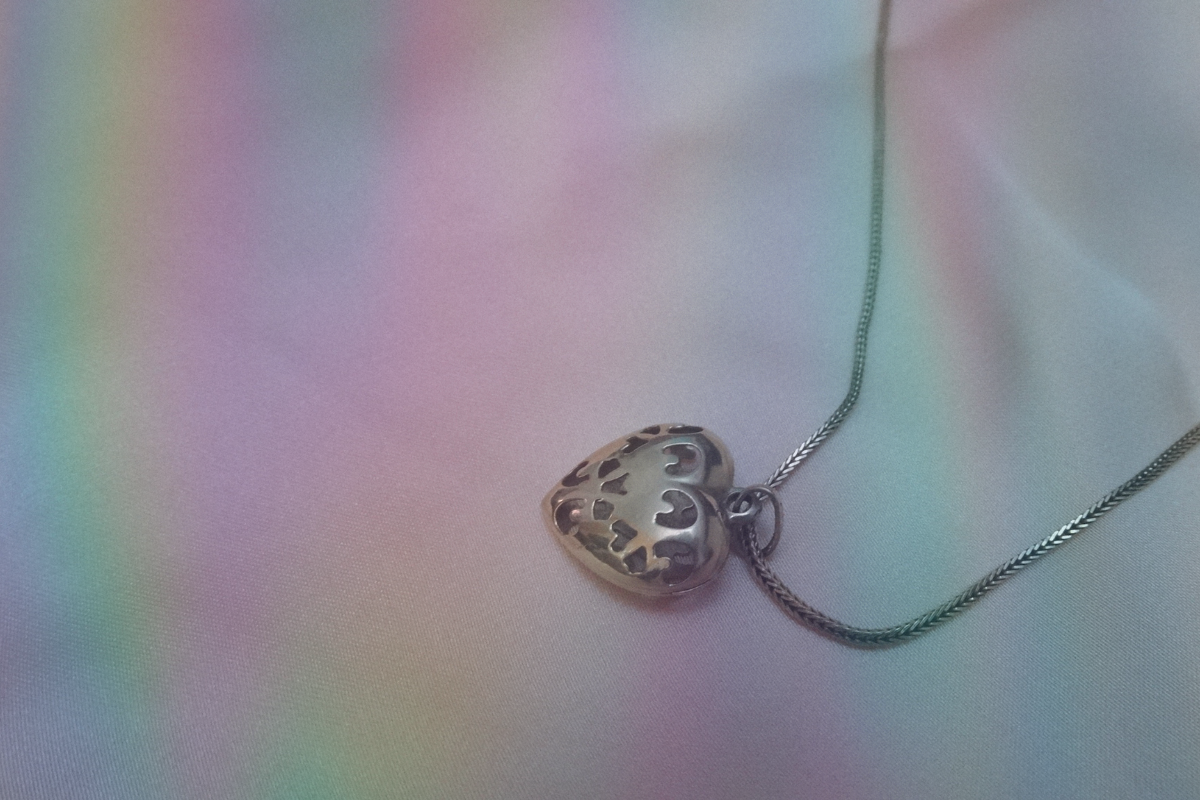

I think about her, Sylvia Sirlin… Nana. She’s with me when I write and can’t move forward until my mind has landed on that just right turn of phrase. I wonder about her years working at Wiley and Sons, a New York City based publishing company that no longer exists, and use her keen eye to trim the excess and adverbs. When I’m stuck, in a story or in life, I wrap my fingers around the gold heart pendant— the one that belonged to her, and to her mother before. I press the etched initials between my thumb and forefinger as if to derive some power from my great grandmother’s initials.

When Nana gave me her mother’s necklace, it wasn’t with much pomp as she was never prone to theatrics. She simply handed it over and told me it made sense for me to have it since I have the same initials as her mother: B.S. I was 14 and felt much more pride about sharing my initials with Britney Spears than Bertha Stone, so unaware of the impact that necklace would have on me. Now I slide the flat, gold heart along its chain and think about how much these women have guided me to this exact spot.

As my fingers move across the keyboard, it’s their hands that wave away the cloud of imposter syndrome and dispel its foggy remnants.

I never met Bertha Stone, as Ashkenazi Jewish tradition instructs to name a baby only after the deceased. Instead, I relied on stories from Nana, who mostly passed along anecdotes about her mother’s prudence and fortitude while raising her and her sister in Queens during the Great Depression.

Never verbose, Bertha showed her love through quieter acts. She balanced the family checkbook and made certain that every penny was accounted for. She prepared Sabbath meals on Austrian china and was attentive to her daughters’ Jewish and secular education. While her standards were “exacting,” as Nana once put it, her encouragement was laced with warmth.

From her came Nana’s respect for the English language, inclusive of proper grammar. Though never a writer, other than the essays she saved from her days at Columbia University, Nana told stories through scrapbooks. She arranged photographs, dance cards, pamphlets and ticket stubs to tell the tale of her teenage and college years. She loved a well-told story and for as long as I can remember, was always part of a book club.

When I was teaching middle school English, Nana would ask what the teenagers were reading. She’d sigh in approval when I mentioned “To Kill a Mockingbird” and scrunch her face at the sci-fi graphic novels, but would show interest all the same. Our shared love of reading connected us, and I often mailed her copies of novels I thought she would enjoy, ones she wouldn’t have to return to the library she frequented.

By the time I mailed her a copy of Anne Tyler’s “French Braid,” her eyes were too tired, and she was sleeping most of the day which frustrated her to no end. She never did get to read Tyler’s multigenerational family saga, but oh how she would have loved its message of the everlasting impact of family: “that’s how families work, too. You think you’re free of them, but you’re never really free; the ripples are crimped in forever.”

When I’ve done something out of character or have momentarily given up on my goals, it’s the ripples of the women in my lineage that pull me back. I wanted to tell Nana that. In the quiet moment when we said goodbye, I wanted to thank her for the necklace, for the namesake that grounds me. I searched for the perfect words to tell her what she meant to me, but in the end, I put my forehead to hers and said, “You were the best.”

Her death is entangled with the lives of her children, and her grandchildren, just as her mother’s was before her. My grandmother’s life is forever braided with mine and I think about the power her name will hold for the baby named for her one day.