The Catskills are so beautiful, and so different from what they used to be.

Driving through the verdant New York mountain range one summer weekend earlier this year, it was hard to imagine that this place, now full of hipster B&Bs and restaurants, was once the heart of Jewish culture and leisure in the country. It was the place where some of the greatest comedians of all time, including Joan Rivers and Mel Brooks, got their start. It was a Jewish safe haven known as the Borscht Belt.

Back in 2016, photographer Marisa Scheinfeld, who grew up in the area, released a book of photos she took of what were once opulent resorts, now abandoned and disintegrating, moss-ridden and eerie. It was a haunting and beautiful tribute to a place that appeared to be all but forgotten.

Yet now, the Catskills are undergoing a renaissance of sorts, both in reality and in our imaginations. In 2018, the beloved Jewish characters of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” took a trip up north. The area has a prominent place in the now streamable Broadway musical “Mr. Saturday Night” starring Billy Crystal. It’s about to be the setting of the upcoming “Dirty Dancing” sequel. It’s inspired several great recent novels and a podcast called “The Borscht Belt Tattler.”

And this summer, the Borscht Belt is undergoing a revival on location, its ghosts brought to prominence and light in new ways. The Borscht Belt Museum which hopes to open its doors in 2025, launched a pop-up in Ellenville, New York, and recently organized a comedy festival that pays tribute to the one-time epicenter of Jewish comedy.

Scheinfeld is part of that effort, spearheading the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project with the help of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. Before she came onto the project, she tells me over Zoom, there wasn’t even “one marker to commemorate the Borscht Belt era in the whole region, which is kind of astounding.”

Erecting colorful signs in different towns along the Catskills that pay tribute to the vibrant Jewish history of the area, Scheinfeld hopes to put up 20 markers that will eventually create a trail that people will be able to follow.

“It’s going to be scattered across the entire Borscht Belt, where people will be able to drive and experience and see the Catskills and go to each town where the Borscht Belt happened,” Scheinfeld says of the project she thinks of as “spreading the love.” A QR code on each sign guides visitors to other nearby attractions, helping to revitalize an area that, in 2020, also became a place of respite for those looking to escape the COVID-19 pandemic in New York. She’s hoping these markers will have a greater appeal to the many tourists who have been visiting the area since then; she’s also working on an audio guide tour to go along with the marker trail.

The first marker was erected in the town of Monticello this past May, along with a screening of the 2012 documentary “Welcome to Kutsher’s” where members of the family that started the iconic resort spoke.

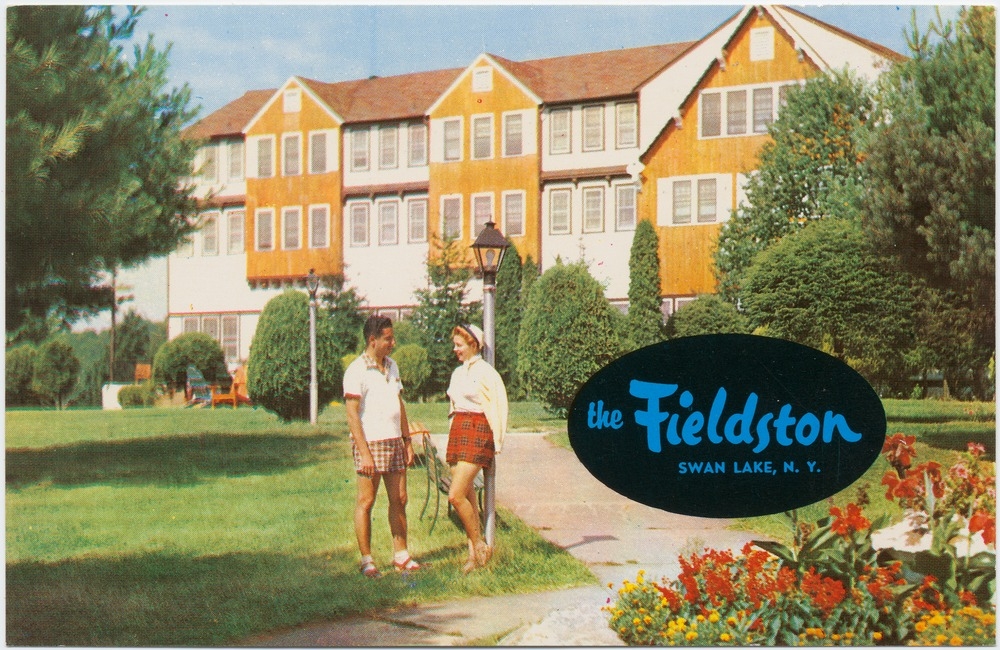

This month, Scheinfeld and the Marker Project will be putting up two more markers — one in Mountain Dale on August 13, and one in Swan Lake on August 20.

“I’ve been invested in the topic of the Borscht Belt for over a decade,” Scheinfeld says. “[It’s] a topic that deserves to be recognized.”

It all started when Scheinfeld was working on her MFA in photography. A professor told her to “shoot what you know.” Her parents moved to the Catskills when she was 5, when her dad took a job in Sullivan County. “He has always said he took that job because he went there as a kid,” Scheinfeld explains. Her grandparents had a condo at Hidden Ridge at Kutsher’s and the kids would go with them to the hotel where they’d watch their grandparents play cards. It was down the road from another resort, the Concord, where a teenaged Scheinfeld worked as a lifeguard the summer before it closed.

“Those are my anecdotes, those are my memories, my family history,” she says. “It became clear that it was the tapestry of my life, this topic.”

While working on her book, Scheinfeld came across places that held deeply personal memories for her, like seeing the pool table where her grandfather played on, still intact (“That made me cry all the way home,” she says). She also came across places where she didn’t grow up visiting, like Grossinger’s, the famous resort that “Dirty Dancing” is based on, which burned down in 2021.

“I would see plants growing up through floors and birds flying through windows. That was surreal,” she says.

“I never looked at the places as looming, ugly ruins. I looked at them as places that stories can be told from — the Jewish story, the Catskills story, the story of its vibrancy and the story of why it was created, which is because of antisemitism.”

The Borscht Belt was created as a safe haven from antisemitism, and its decline started in the ’60s following the Anti-Discrimination Act, which meant Jews and other minorities suddenly could go to the resorts they’d always been banned from.

Scheinfeld first received an offer to work on the Marker Project years ago, when she was pregnant with her first child. She’s recently given birth to her second child, a daughter named Goldie, and being able to do this project as a parent has meant even more to her.

“It’s been fun to watch [my son] as I’m speaking or as I’m working on this and be like, ‘What is mom doing?’ I keep telling him I’m making a driving tour because he loves to drive, and he loves to ride in the car. So he’s like, ‘Can I help? What can I do?’ It’s something that I’m really excited to teach him about too, because I named him after my Grandpa Jack. I’m excited to teach him about our family history and where I grew up.”

Scheinfeld, who lives in Katonah, New York, not far from her parents’ home in the Borscht Belt area, is also working on a new book about unknown and unseen histories of the Catskills and the Hudson Valley. It’s called “Once Upon a Time” and it’s about “these places that maybe you drive by, and you don’t notice.” In researching it, she discovered that back in the 1800s, the Catskills was home to another Jewish place of hopeful reprieve: a Jewish community called Sholem. “It was the first Jewish agricultural community in the entire country.”

“They started it before the railroads were built in the Catskills and it ultimately failed. But it was supposed to be this Jewish utopian community where they were self-sustainable.”

The markers, for Scheinfeld, are educational, but they’re also a celebration — the Catskills are alive now, full of vibrant places for tourists to visit, coffee shops for tired hikers to rest, and diners to enjoy a new take on a nostalgic treat.

“I think what’s going on in the Catskills is a renaissance. And when a renaissance happens, people are more likely to look at the past,” Scheinfeld explains. “In the case of the Borscht Belt, it had a demise, it failed, it crashed and burned. So now with this wonderful future ahead, to look back at the past, we can celebrate it. It’s not a symbol of failure. We don’t see the county stagnating with these ruins anymore. We see new buildings, new structures, new boutique hotels, new restaurants, and then, well, look at these markers. Look at this history. Look at these places we can remember.”