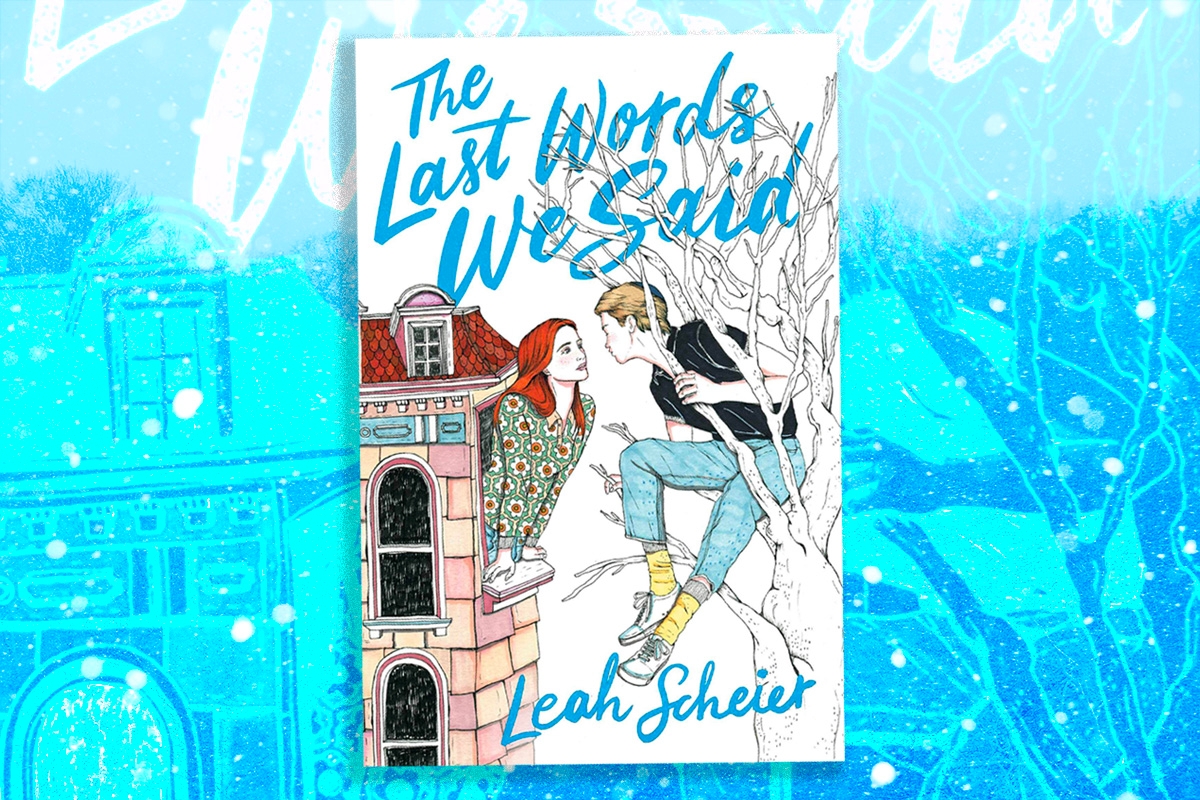

The first thing that struck me about “The Last Words We Said,” a young adult novel by Leah Scheier that came out last summer, is its arresting cover illustration. A boy sits on a tree, wearing a yarmulke, leaning over to a modestly dressed girl in the window with long red hair and ruddy cheeks, their eyes locked on each other. It’s rare to see a Jew wearing a kippah on the cover of a book — especially on such a romantic, lyrical one.

The contents of the book are just as arresting. It’s a heart-rending tale of grief and loss that focuses on Ellie, a teen grappling with the disappearance of her boyfriend, Danny. Ellie refuses to accept that the boy she loved is forever gone — she sees and talks to his ghost. Her two other best friends, Deenie and Rae, deal with the loss in very different ways.

The characters in this book are Modern Orthodox, a rarity in pop culture and fiction and specifically in young adult fiction. The majority of depictions of Jewish Orthodoxy tend to swing toward the ultra-Orthodox end of the spectrum, yet Modern Orthodox Jews, who attempt to balance traditional observance of Jewish law with modern society and endorse secular studies, comprise around one third of the Orthodox Jewish population in the United States.

This is Scheier’s fourth young adult novel, but the first in which she chose to tell a story about her own community. The book offers very transparent and honest insights into a significant swath of the Jewish community, those who don’t fall into the extremes of being either secular and fully assimilated or ultra-Orthodox and completely isolated. Yet despite the specificities of the culture in which it’s set, “The Last Words We Said” is a universal coming-of-age tale highlighting the clash between the values you were raised with and the realities of life and love and friendship and pain as an adult.

Kveller talked to Scheier about what made her feel ready to write this story and about her feelings on Jewish representation in the media.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Tell me a little bit about the book cover! It’s so striking and I do feel like it’s rare to have a character wearing a kippah on the cover.

“The Last Words We Said” is my fourth published novel but it was the first time my publisher asked me for input and suggestions [on the cover]. They sent me a mock-up and when I saw the kippah, I freaked out. At first in a good way — I can’t believe there’s a teen boy with a kippah on the cover! And then, I admit I got a little nervous. What if the kippah alienated non-religious and non-Jewish readers? What if they didn’t pick up the novel because they believed it to be a “religion” book that they wouldn’t relate to? Thanks to my agent, Rena, who told me, “I would have given anything to have seen a cover like this when I was a teen,” I realized that the Jewish rep in this book is something that needs to be cherished and celebrated, not hidden.

How did you realize that you were ready to write a book that immersed itself in the Modern Orthodox community?

For the longest time, when people asked me if I was ever going to write a book about my own community, I always gave an emphatic no. I didn’t believe I could ever portray something so close to me in an objective fashion. I can’t stand novels where the author’s religious or political beliefs “leak” into the characters’ lives. I call it fictional propaganda and I find it to be so off-putting. It wasn’t until my four characters started speaking to me that I recognized that I loved and respected each one of them, despite the fact that they all had such different relationships with their community and Jewish faith. I knew then that I could write their story in an unbiased way, unclouded by judgment. It was so important to me to portray my community with love; religious communities are so often portrayed in a negative light by the media, and that just fuels division between people, both religious and non-religious.

Was it hard to sell a book with such detailed religious representation?

Were there rejections? Absolutely! I’m not sure if the religious representation was the reason, though. As an author, you rarely find out the reasons your work was rejected. But a wonderful editor at Simon & Schuster, Liesa Abrams, bought the novel because of the Jewish rep. So, it worked out just fine.

How did you decide on the level of details about religious observance to include in the book?

It came about rather organically. I wanted the climactic events to happen around the High Holidays, specifically Yom Kippur. When I included customs, Yiddishisms or terms that a non-Jewish reader wouldn’t know, I made sure it could be understood through context. Of course, I couldn’t have the characters explain their own culture out loud, as they would never do that in real life, so if a bit of dialogue felt obscure at all, I changed it or eliminated it. (There’s also a brief glossary at the back of the novel if the reader is curious about the exact meaning of a word — but it really isn’t necessary to refer to it.) The key was to make the Jewish traditions feel natural, even to someone who knows nothing about Judaism.

Deenie’s father, Rabbi Garner, is the one figure in the book who’s a religious authority, but he’s also represented as so human and flawed. What was the inspiration behind this character?

Just as religious communities are so often portrayed in a negative light in movies and books (think “Unorthodox” or “My Unorthodox Life”), so are clergy. How often do we see clergy members revealed to be monsters by the end of a film? In fact, clergy holds a very important place in many people’s lives and they are, for the most part, kind, caring folk who have dedicated their lives to healing. But of course, that doesn’t make for a very exciting “twist.” In my novel, Rabbi Garner is a good if imperfect man. I wasn’t interested in creating an angel or a monster when I wrote him. Just a kind human being.

There aren’t a lot of books out there with Modern Orthodox representation, especially not this level of representation. Was that something you spent a lot of time thinking about? Did you feel like you had some larger responsibility to represent the community in a certain way?

I wanted non-religious teens to read my book and identify with my characters, even if they’d never stepped inside a church, synagogue or mosque. And I wanted to break the stereotype of the religious Jew as an extremist shut off from the world. I’ve never seen Modern Orthodox Jews portrayed in traditionally published books or in film. Secular Jews are portrayed all the time, which is great. And ultra-Orthodox and Hasidic Jews are as well, though rarely in a positive way. Yet, my community is largely ignored. So many non-Jewish readers have written to me saying that they didn’t even know Modern Orthodox Jews exist. And so many Jewish readers have written saying that they finally saw themselves in a novel!

This book is also about the tension between the ideals of observance and human sexuality. It’s a point of tension in religion, in general, but I do think there’s a lot of fetishization of that when it comes to Jewish Orthodoxy (thinking about how initially put off I was by “My Unorthodox Life” because the first thing they talked about was sex and I was like, really?!). Was that something you were thinking about as you were writing this book?

I never even started “My Unorthodox Life” because I’d read enough about it to know what was coming and I’m honestly just tired of it. To illustrate how pervasive this fetishization is — both a relative and a friend (both religious Jews) asked me if I intended the scene where Ellie and Danny kiss through a blanket to allude to the “sex through a hole in the sheet” myth. I was absolutely floored! No! It was just a scene about two teens who were struggling to be “shomer” [observing the prohibition on touching] and tried to bend the rules a bit. The “hole in the sheet” is a nasty myth about Hasidim which has no basis in truth. I would never refer to it or give it any support. So I suppose the short answer is that I didn’t really think of the fetishization aspect at all while writing, but now that the book is out, I can’t avoid it.

Names — and particularly Jewish names — play a central role in this book. Jewish baby names are kind of our bread and butter here at Kveller, so I was wondering if you could talk more about what went behind choosing the names of the characters and why it was important for you to make that a focal point?

Ellie’s Hebrew name, Eliana Tikva, means “God has answered my hope,” which is how her parents related to her throughout the book. She was their pride and joy, their only child, and so they invested everything in her. But that also put a lot of pressure on her and sometimes she didn’t feel like she was living up to their expectations. Deenie’s name means “gentle song,” which is the part of herself she is trying to stifle throughout the novel. Rae rejects her given name completely. And Danny’s full name isn’t revealed until the end of the book, but it is also meaningful.

I didn’t exactly intend to make names a focal point; it was more of a theme that spoke to the different influences on our lives. Just as religion, faith and friendship inform my characters’ choices, so do their names, whether they embrace them, or try to run away from them.

What are your hopes and dreams when it comes to religious representation in books? What would you like to see more of?

I hope for more books about all kinds of Jews, religious and non-religious alike. My agent is representing a book about an Orthodox teen boy, “The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen,” which is due to release in the spring from Penguin. Besides that upcoming release and my book, I’m not aware of any books featuring Orthodox Jewish teenagers in traditionally published YA.

What are you hoping that people will take from this book?

It’s a little bit different now from when I first started writing it — maybe because of the recent political climate and the rise of antisemitic attacks. The book doesn’t have much about antisemitism in it at all and that was my intention because the whole point was just to represent a Modern Orthodox community. Growing up, we were pretty shielded from overt antisemitism. Now that I’m able to see more of it in the news, it’s disturbing and frightening.

What I want is for teenagers to read about kids just like themselves in a Modern Orthodox Jewish community and say, hey, they’re just like me. It’ll shine a light on the fact that we’re all just dealing with the same stuff in slightly different shades. I want my readers to fall in love with the characters irrespective of their religion and hope for the best for them.