My mother’s ritual was the same every day. When we got home from school, she took off her girdle and stockings, threw them on her bedroom chair and donned what was back then called a housecoat. Then she would head into the kitchen to make a fresh pot of coffee and put a selection of baked goods on a serving plate.

Ten minutes later, the doorbell would ring and my mother would open the door for her friend Rose, who lived around the corner. They must have had some kind of psychic signal because Rose invariably arrived the moment the coffee was ready.

Once they were settled at the table having their daily afternoon chat, it was my time to strike. This was when I was most likely to get my mother to let me do something she would normally disapprove of, whether it was watching TV before I did my homework, skipping my hour of piano practice or going across the street to my friend Barbara’s house before dinner. My mother taught first grade and wanted a respite from all children, including myself and my two siblings. She also didn’t like having her tete-a-tete with Rose interrupted with can I… questions.

As expected, she would first say “no” to my request, but it didn’t take much nagging to get her to give up. In a tired, irritated voice she would say, “Fine. Do what you want. Gai fardrai zein ein kop.” Translated from Yiddish: Go drive yourself crazy. Mission accomplished!

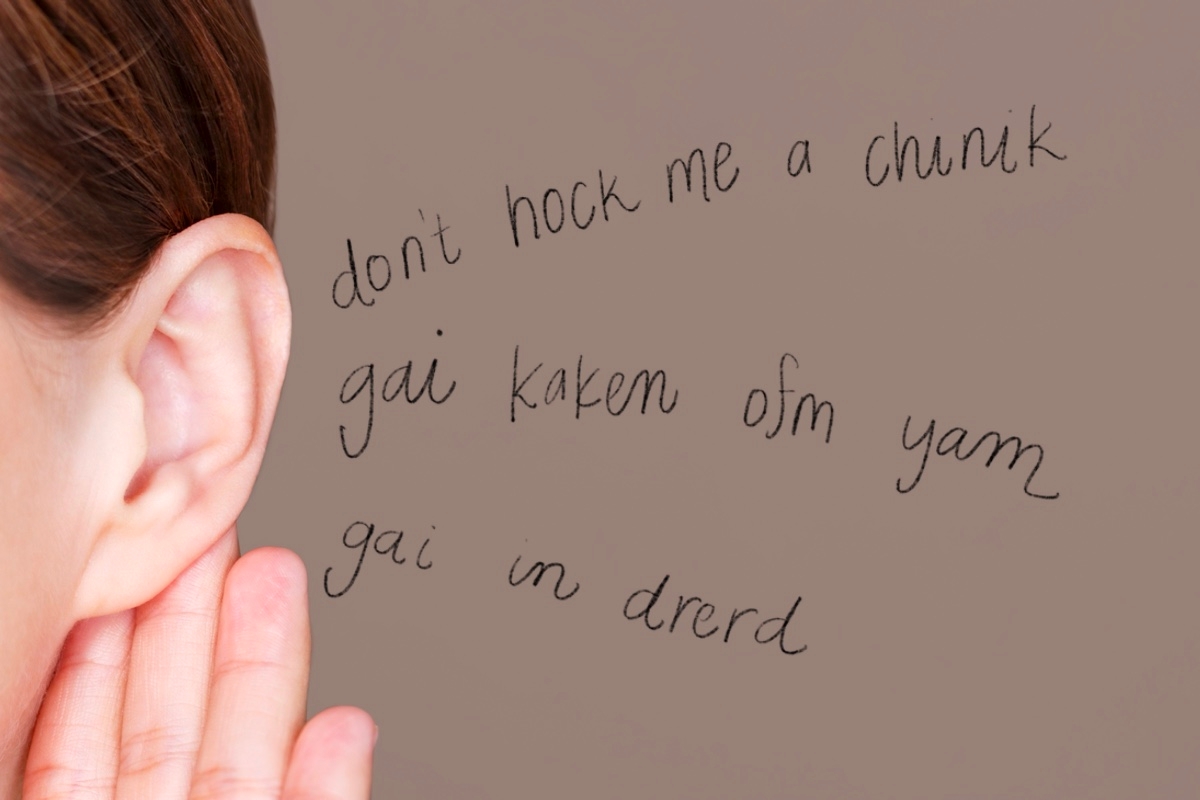

Similarly, there were times we were being reprimanded for some wrong we had done and, finally, thoroughly disgusted and bored with the pathetic pile of excuses (or sometimes out-and-out lies) we were coming up with, she would say, “Don’t hock me a chinik. I’m not interested in your whole mishegas. Just stop doing it!” Literally, “to hock a chinik” means to rattle the tea kettle, but in the vernacular it basically means to get on one’s nerves or give one a headache; and “mishegas” is craziness.

These commands were completely comprehensible. Having grown up in a Jewish American household, Yiddish remarks were mother’s milk to me and my siblings. Both my parents were born in the United States but my mother’s mother, who lived with us, was a Polish immigrant. She had come to this country as a girl of 15 and was perfectly fluent in English, but Yiddish remained a mainstay for certain comments and private discussions.

My grandmother and mother spoke Yiddish when they didn’t want my siblings and I to understand – often when it had to do with one of us – so they never taught us to speak it. They were apparently unaware, however, that children absorb language like a sponge. And that their secrecy made us even more determined to understand Yiddish. We became experts at eavesdropping while looking innocent.

There was a lot of code-switching, which refers to two languages mixed together in a sentence, not only between my mother and grandmother, but also when either of them spoke to us. We did not find it strange; often, we found it amusing. Mostly privately, but also at times in front of her, we would laugh about some of my mother’s more outrageous Yiddish utterances, which, to this day, we still do while reminiscing.

One such utterance often employed by my mother was a curse: “He/she should only gai kaken ofm yom.” (He/she should go shit in the ocean.) My sister and I puzzled over this one. Why the ocean? Our best guess was because Yiddish was transported when Jews from Eastern European countries immigrated to America. With the exception of Russia, these countries were inland. Hence, shitting in the ocean would be akin to wishing they go far away – though not as far as to “gai in drerd,” which means go to hell.

One of my favorite examples of code-switching was told to me by my sister. Home from college for the summer, her Irish boyfriend Patrick picked her up to go somewhere. (My mother must have been getting more liberal; in my day, I was not allowed to date “a sheygetz.”) My sister, with Patrick in tow, came into the kitchen to tell my mother they were leaving. She was wearing a cropped tank top and cut off, hip-hugger jeans. My mother looked her up and down and exclaimed, “You’re going out in that schmatte with your pippick hanging out?”

Although from the tone of her voice it was clear that whatever she had said was not complimentary, and might possibly be about him, Patrick was dying to know what she said. “What did she say you were wearing? What’s a pippick?”

My sister translated. “She said, ‘You’re going out in that rag with you belly button hanging out?’”

This story further convinced me that Yiddish the best language for insults and curses, all of which must be spoken in an appropriately scoffing, disdainful tone of voice.

To this day, I find myself sprinkling my conversations with my mother’s favorite Yiddish insults here and there. Beyond colorful curses, however, Yiddish is a rich, evocative language – an embodiment of Jewish culture that comes from the depths of the gut and the spirit of a noble people who, over the centuries, have courageously survived an array of adverse circumstances. I am blessed to have grown up in a household that embraced it.