As I search in vain for Lysol, or watch people squirt Purell in their palms, or worry about who’s doing what in my social pod, I’m not thinking about Covid-19.

Instead, I’m thinking of my father’s voice, husky from decades of cigars. “Wash your hands!” He’d always say. “Germs will make you sick! Don’t touch your face!”

My father, unlike most of his peers born in 1908, feared germs and infection more than fire or famine. Our home was Jewish but he raised my brother and me in the religion of germaphobery. It was once a lonely place, but now, 10 months into the coronavirus pandemic, it’s a church with no walls and global attendance.

If Papa were here today, I’m pretty sure he’d be gloating over the advice the CDC is doling out to help combat Covid-19. He was no medical expert but he was a voracious reader — and, as he often reminded us, “I know what I know.” He loved to be right — even when he was wrong — which is why we didn’t take his admonitions seriously. The stories he told my brother and me at mealtime were about kids whose innocent-looking scratches turned into deadly infections or relatives whose lax personal hygiene portended disaster. Necessity and adversity were the twin teachers that had schooled him on all things potentially fatal.

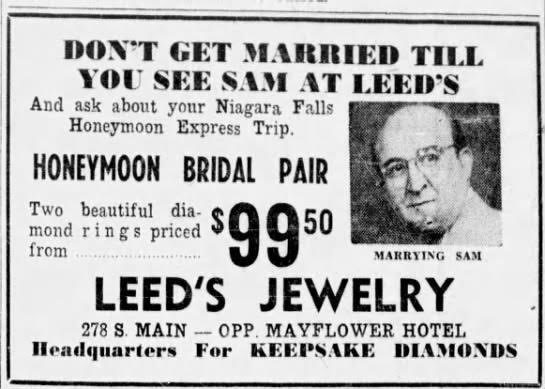

Our friends and neighbors in the mid-century Midwest would have been surprised by my father’s dark thoughts. To outsiders, he was the quintessential cheerful salesman. My mother, the daughter of Russian immigrants, confided once that she fell in love with Dad’s charisma, and he sold her on a life full of American adventure. They owned and ran a jewelry store, and on local billboards, newspapers, and radio ads, he was the jocular “Marrying Sam, The Diamond Man.” Customers and others raved about his charm and easy laughter.

We saw another side of him, however. To our dad, hygiene was more than a concern; it was a preoccupation bordering on obsession. He made a great show of pressing elevator buttons with his elbow. He pushed doors open with his hip and closed them with his foot. Public bathrooms demanded their own choreography; for years, I thought everyone using the commode reached back to flush with their elbow. It could be painful, but my mother, brother, and I did as we were told. His tales of vermin and disease in public restrooms haunt me to this day.

As I got older, I began to understand Papa’s reasons for exercising such caution. He was born to a poor Jewish family in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and emigrated to America with his mother, my Grandma, when he was 4 years old. To survive, Grandma rented dilapidated homes and took in a succession of upstairs boarders, while she lived in a dank cellar with her rapidly-growing family (eventually there were seven children), hovering around a coal stove for warmth. Stray cats kept the rats in check. My father told me that he never felt clean.

Grandpa — who arrived in the U.S. one year after his wife and children — couldn’t take the squalor and was not around much. He left my dad, the eldest boy, in charge, but Papa was too young for any job other than a newsboy, and so there was no money. When one of the kids got sick, Grandma’s preventive medicine included tying rotting heads of garlic in a cloth bag tied around her neck, lots of Yiddish prayers, and other old wives’ tales to keep “the evil eye” at bay.

Those invocations were no match for the harsh winters of Akron, Ohio. All seven kids always had runny noses and coughing fits.

My father was used to it. But one day he noticed an angry, tangerine-sized growth behind his ear. He was too busy selling newspapers and tending to younger siblings to focus on his own medical needs. When pain finally overtook him, he walked to the emergency room where a nurse quickly lanced it — and Papa watched with horror as its contents exploded all over him like hot lava. It was mastitis, an inflamed gland behind his ear. In that nightmare moment, alone and without an understanding of what was happening to him, fear took root. No matter how wealthy, successful, or beloved he was, he never shook it. He quoted the nurse’s words to us frequently: “An infection never cures itself. It always gets worse.”

In a way, the mastitis never left him, and neither did the understanding that death and disease were ever-present.

Fast forward to any family dinner in our 1950s picture-perfect home. If one of us accidentally touched our face, we got the “triangle of death” lecture. “It all starts innocently enough,” he would begin, like a mystical storyteller weaving a tale. “A scratch, a pimple, a cut… Picking with dirty hands is all it takes to start an infection that directly affects the brain. And boom! That’s it. You’re a goner.”

He’d slam his hand on the table, and the silverware jumped to attention.

“A goner?” I asked, warily clutching my mother’s hand. Undaunted, he continued. “Yup. DEAD. FINITO. Fini.”

“Sam, stop it,” Mother interrupted. “You’re scaring them.”

“Am I lying?” he would ask indignantly. “I’m just trying to keep them healthy.”

“I know, dear, but can’t we do it more softly?”

Not my dad. He seemed unable to turn down the volume.

As an adult, I was shocked to learn that the triangle of death is real. Medical literature describes the infection-vulnerable area between the top of the nose to the bottom of the lips. All those years, I had considered his obsession a form of mild insanity — but now, through the blurry prism of time, I see that he loved us so much that it literally hurt. There was emotional pain, a lot of screaming, and many tears in our home. His anxiety seemed contagious. I can remember my mother’s hands trembling when he started down a path she knew would end badly.

Papa was a complicated man, but he could find humor in the smallest things. Often, we both laughed so hard that I almost wet my pants. Sometimes, he would wake me in the night and carry me to the bathroom window to see a beautiful, full moon. He convinced me that if we squinted just right, we could see the man on the moon. His unique magic and thirst for knowledge transformed otherwise forgettable moments into unforgettable memories, and he turned the most mundane vacations into fabulous adventures.

Still, the filth and poverty of his childhood, and hazy recollections of neighbors dying during the Spanish Flu of 1918, instilled in him feelings of anxiety and powerlessness that stirred up emotional havoc for decades.

But for a dutiful daughter like me, it also created habits — like regular, proper handwashing and an encyclopedic knowledge of antibacterial products — that have helped me manage during the pandemic. Although there was stress, worry, and anger in our home, the memories that stick with me are ones of his immaculate, soft hands, cradling my face, wrapped in the fragrance of clean, fresh soap.

I wish I could thank him for all that he’s given me, and to assure him that, especially during this deadly pandemic, I am not touching my face.

Header image by z_wei/Getty Images; “Marrying Sam” image courtesy of the author