Jo Ivester is an award-winning author of the inspirational memoir The Outskirts of Hope. It’s about her family’s experiences as the only Jewish family living and working in an all-Black town in Mississippi in the 1960s.

Her childhood experiences inspired her to become a civil rights activist. As Jo tells Kveller: “First, I developed an awareness that prejudice and discrimination exist and need to be battled. Second, I found the courage to be a part of that battle. And third, I recognized that one individual could make a difference.”

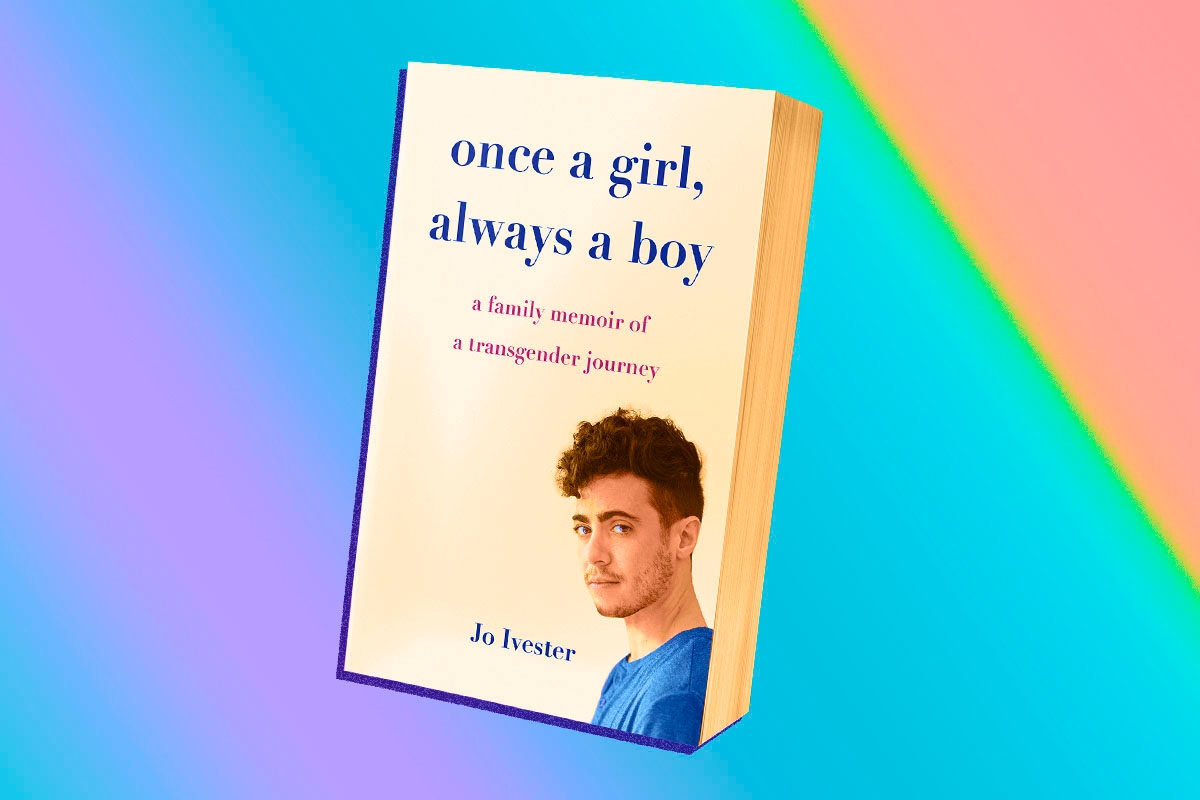

She has now come full circle, applying these same principles to her latest book, Once a Girl, Always a Boy, which chronicles the journey of her transgender son, Jeremy, from his childhood to how he became an advocate for the transgender community. A unique “family memoir,” the book is told from multiple family members’ perspectives. Library Journal recently called the memoir “a model for other families searching for acceptance and ways to support their loved one’s transition journey.”

We chatted with Jo about her motivations for writing the book, what it felt like to get her family on board for this project, and how Jewish communities can be more inclusive and welcoming to transgender families.

What inspired you to write this book?

When I wrote my first book, The Outskirts of Hope, it unexpectedly gave me a platform from which to raise awareness about racial relations. By sharing my family’s stories — we were one of two white families in our town, and the only Jewish one — I was able to encourage people to stretch their comfort zones and acknowledge that discrimination and prejudice still exist today, and that we can individually do something and make a difference.

Those lessons of civil rights advocacy prepared me well when, over 40 years later, I learned that my son is transgender. I was able to move very quickly from a total lack of awareness of what it means to be transgender to becoming an advocate, fighting against prejudice and discrimination, and fighting for equal rights. By sharing my son’s story, I could make people understand that being transgender is “real” and that transgender people deserve the same dignity and respect that we all crave.

One of the unique things about this book is that it’s told from different perspectives. Why did you make this choice?

My book is not only my son’s story of growing up in a world not quite ready to accept people like him. It’s also that of the entire family — specifically both parents; his brothers, Sammy and Ben; his sister, Elizabeth; his sister-in-law, Jenn, and his Grandma Aura — as we struggled to understand what it meant to have gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria is the distress that someone feels when their sense of gender doesn’t match the biological sex assigned to them at birth; biological sex is a label that’s typically assigned by a doctor at birth, based on external genitalia and chromosomes.

Over 40 percent of transgender teens have attempted to take their life. Gender dysphoria is very difficult to deal with and individuals who do not have the support of their family suffer tremendously. I thought that by bringing in the voices of siblings and parents, as well as Jeremy’s own voice, it would make it easier for the family members of trans individuals to relate and accept.

What was the process like in getting your family on board for this project? It seems really special for a son to allow his mom to tell such a personal story. What kinds of conversations did you have with Jeremy and your family about this process? How did you balance what to share with what’s needed to protect your family?

Jeremy understood immediately why I wanted to write about him. Although he is a private, introverted individual, he was willing to forgo his privacy in order to help others. Before he even asked, I assured him that I would seek his approval on every word of the manuscript; I would not include anything that he’d rather I not share; and I’d give him veto power the entire time. That gave him a sense that he could trust me. He rarely limited me, but he did draw some boundaries.

For the rest of the family, it took longer to trust that I could write something they would be OK with sharing with the rest of the world. [They were] aware that it had taken them some time to accept Jeremy’s journey, they worried that their early lack of understanding would make them appear unsupportive. In fact, they were supportive from the beginning — the love was always there. But Jeremy kept everything so bottled up inside that his siblings couldn’t begin to comprehend the extent of the journey he had undertaken. Even after he began sharing more openly with them, he was still in such a state of denial that he kept saying, “This is the last step.” Yet his journey continued. This taking of baby steps, as Jeremy puts it, made it tougher for his siblings because they kept thinking the journey was complete.

How has your relationship with Jeremy and your family evolved during the process of writing this book?

The writing process drew the family closer together. Because anecdotes were initially written only from Jeremy’s perspective, they sometimes surprised his siblings. Memories that were critically important to Jeremy had been forgotten by his brothers and sister. Moments that he saw as painful, they saw as minor conversations.

Did you learn anything surprising while working together?

As everyone reviewed the manuscript and talked about it, all of that came out and everyone spoke openly with one another. Walls that they didn’t even know existed came down.

One of the Jewish values you have instilled in your work beginning with your first memoir is that of tikkun olam — repairing the world. What are some of the ways your memoir illustrates these values?

The world has not yet accepted the reality that some people are transgender. Politicians make political points by passing discriminatory bills and trying to force trans individuals underground. If some politicians had their way, my son would not be allowed to work, to rent his apartment, to receive medical care, to adopt a child. The world is broken. By sharing Jeremy’s story, I hope to illustrate that this is still happening today and that we all must do our part to fix things.

How can the Jewish community do better when it comes to being inclusive and supportive of trans people?

Many Jewish communities are already doing a wonderful job of accepting their transgender community members, of respecting differences between people, of supporting those who are marginalized. I am heartened by the support we’ve experienced from the Anti-Defamation League, from JCCs, from Keshet, from the Federations, from Jewish film festivals. But there is always more that can be done. Individuals can take a stand whenever they hear someone denigrate a trans person. We can approach our schools and politicians to put in place policies that support our transgender youth. And if our elected and appointed leaders fail to do so, we must vote them out of office and find leaders who are willing to respect everyone. We can provide financial support to organizations that fight for the rights of transgender people. We can listen to the stories of those who have been marginalized and demonstrate our respect.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

I hope that readers will develop a true fondness for Jeremy and his siblings, and that they will understand that Jeremy is a real person, deserving of love and dignity. That he is normal. By letting Jeremy into their lives and hearts, readers can raise their awareness of what it means to be transgender. I have to believe that with that increased awareness, we will find increased acceptance. Only then will we truly experience tikkun olam.

Header image via Jo Ivester